The promise of productive failure in an English Language Arts classroom.

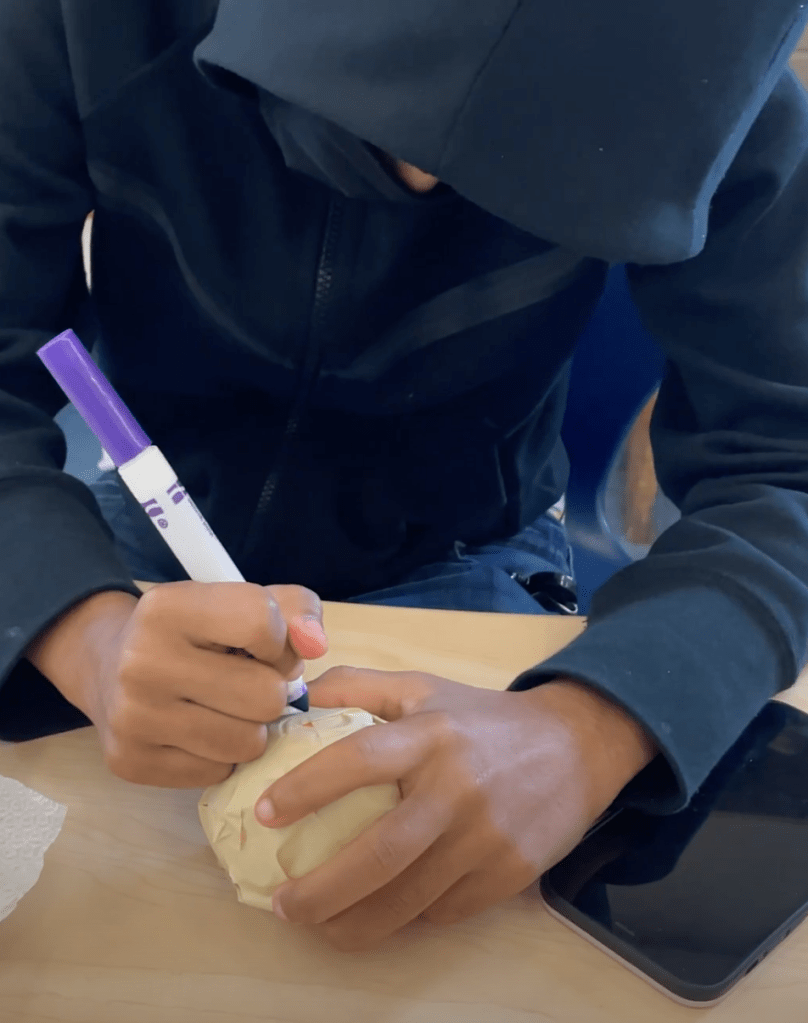

On the first day of summer school last July, I handed each student an orange with the instructions to peel it…very slowly. Some students asked why. Others started immediately. I heard talking as they peeled and laughing when someone asked, “Can I eat the orange?” After everyone was finished peeling, I said, “Okay, now, put it back together.” Inevitably, there were a lot more “Why’s,” and they were a lot louder. I heard a version of “Are you kidding me?” I held firm. “You can do it. This is your only job at this moment. Figure it out.” I walked to each table with a 4-foot long strip of tape for each student.

When I heard students say, “This won’t work!” I questioned, “How do you know?”

I teach the orange lesson as a metaphor for pushing boundaries, taking risks in learning, and building resilience with the idea of understanding something that pushes against our comfort levels of what [we think we know] we can do. We know what peeling an orange feels like, and we know the outcome of that action. We don’t know—or yet understand—the process of putting an orange back together again. That unknown act requires trust that the process will yield a certain outcome. It also requires vulnerability for playing our part in that process.

Last July, for the thirty students in front of me who had failed English multiple times over multiple years, I framed it as “unlearning” in the sense that sometimes we must “undo” what we know to move forward and take on new challenges. I asked my students, “Why might unlearning be something we want to try when working with something challenging?” One student raised his hand, “You can’t ‘unlearn.’ You can re-learn, but once you know something, you can never not know it.” I wanted to jump up and down. If there had been any hesitation at spending July and August in a classroom without windows, I could not remember it at that moment.

I learned valuable information about my students as I observed how they put their orange back together.

In the growth mindset Ted Talks I play for students, there is an explicit message: Fail first; fail often.

With a growth mindset, failure is a right of passage. However, the longer I teach writing to students who supposedly “don’t do school,” the more I recognize that writing is about students giving themselves permission to fail. Each day with my students I see how even the thought of failure stops writing before it starts. In order to assume that “failure” is a conduit of creating and composing, we need to believe that we will recover from failure, and further, that we will be protected from the aftermath of having failed. For some students, failure is a right of passage that feels like a set-up. From a restorative teaching lens, failure is an option that students are less likely to choose if compassion is less visible in their learning environments both in and out of school.

When we teach writing with a restorative lens, as a way to change student mindset, we affirm for students that they are worthy of failure as a means of growth.

I’ve struggled with ways to integrate trauma-informed teaching and restorative practice into my daily lessons until I experimented with ways to integrate that mindset into the teaching of writing. Teaching writing is reliant on a learning environment, rich in affirmation, that prioritizes relationships as a driver of teaching and learning. As Zaretta Hammond points out in Culturally Relevant Teaching and the Brain, this relational piece is what gets students to jump into the work of learning, right into the learning pit. Teaching writing has the effect of revising how our brains are wired, shaping a different way of thinking through learning challenges and productive struggle. Teaching writing is restorative practice.

In that same summer school classroom, I was reminded of how writing is a change-agent, re-visioning how students think about themselves as contributors to the world. One student in particular defied the stereotype of being labeled a failure, learning that he is, in fact, a writer. He wrote a 30-page memoir over four weeks as credit recovery for failing sophomore English.

But first he needed to realize the relevance of writing his story, and I needed to convince him to show up to summer school every single day.

“You should write a book.”

“Why would I do that?”

“So people can see what you see.”

We closed the deal with my offer: “If you write your book, you’ll earn passing credit for ELA. All you have to do is show up and write.”

His response: “F- it. Let’s do it.”

Every day I am driven by the question of how to engage students who are stuck in a cycle of failure.

Most of my students have failed, multiple times over multiple years, and are labeled by nearly everyone around them as failures. They carry around with them the long list of people who have told them something like, “I’m done with you. I can’t do anything to help you anymore.” The collegial advice I dread is the notion that “sometimes the kid just has to hit rock bottom, and that’s the best thing for them.” At what point does this also mean giving up on a student? Failure is a missed opportunity when we ignore it, or worse, ignore the students who have failed. When we don’t talk about failure, students get stuck and teachers get frustrated, observing engagement move from ritual compliance to, well, nothing.

As a teacher, I needed to learn to work with failure, not against it.

I began the work of facilitating memoir writing with my student and dug into Manu Kapur’s idea of productive failure, productive struggle 2.0: Set up the problem and step back. Thinking about Kapur’s notion of productive failure, I reframed instructional strategies to create opportunities for failure in my lessons. Here’s how I see this play out in my classroom: If I’ve set up learning with productive struggle in mind, I’ve already hit the trifecta of rigor, cognitive demand, and student-centered learning. Productive failure is that intentional instructional shift that starts before the student begins. In lesson design, productive failure requires letting go of the “plan” to get the student from A to B by C and allows the student space to problem solve with re-directions rather than directions.

There’s a voice in my head that still questions the risk of failure by design. Edutopia’s September 2022 interview with Kapur, If You’re Not Failing, You’re Not Learning, affirmed the practice of designing for failure, indicating quantifiable gains in learning outcomes. Similarly, in the Jenny Anderson’s New York Times article Learning the Right Way to Struggle, productive struggle is paired with Kapur’s research on productive failure, where problem solving before learning how to do something produced learning outcomes that changed the brain.

Although mostly associated with STEM, productive failure is exactly the work of writing as there is no way to fully understand how to write until you go through the motions of writing.

There is no ready-made, visible path. Yes, there are graphic organizers and stems and brainstorming and think-alouds, but there’s no guarantee of the end product exactly as it will be written. For my student writing his memoir, the productive failure was inherent in the act of composing and figuring out: How do I get what is already living inside my head, from my head to my hands, to the page, and to keep that momentum going to compose a story? The path of productive failure is circuitous; it leaves ambiguity within a void of either nothing (denial and quitting) or something new (embracing opportunity).

I pushed my student to provide more detail, which became one point of productive struggle within a process of productive failure.

Over July and August my student began the work of writing as problem solving, moving forward without knowing what is ahead. But, first he needed to show up. He asked for a morning text to help get him to school, and I followed up every day with a positive note.

During revision I asked questions:

“Why do you think that happened? What were you expecting instead? How do you think things would be different if…” My questions, “What does it sound like? What do you see around you?”

“How do you know it’s X and not Y?” marked a frustration point to which he responded, “This is making me tight. I’m not doing that. It’s just clear in my head.” And I countered, “But it’s in your head, not mine, so you have to make me believe it.” At each point my student stopped with, “This isn’t going to work. I can’t do this.” I responded, “You’re already doing this. Keep going.”

It took a month of writing every day for him to realize that writing the vignettes of his life—and making them stick with the reader through vivid imagery, dialogue, and detail—was a wall that he broke through to get to the other side of what he thought he was capable of before he started. But each break-through moment was matched by a moment of giving up as he said things like, “Why are you helping me? I don’t deserve this. Everyone says I’m a piece of shit.” I sat with that without saying anything so he could be heard. I saw people, educators, treat him just the way he saw himself in that moment of meeting his frustration level. At that moment he knew exactly how to quit. Most of my students choose quitting over failing; quitting prevents them from even starting, making quitting their safety net.

My student met his frustration level because he didn’t have the road map in front of him to tell him how to get the thoughts in his head to the page.

James Nottingham’s Learning Pit as pictured by The Great Work Lab

Meeting and naming his frustration was the part of the writing process that proved to him that he could persist. So his response, “This is making me tight,” is met with: “Describe what you are feeling” or “What do you need right now to push through?” or “Tell me why,” before I asked “What is your next step?” or “Okay, so that didn’t work. What can you try instead?” My strategy was for my student to be able to name the frustration, acknowledge how it impacts his writing, and move beyond it. When I teach writing, I am upfront with students that the urge to quit is real; it is normal, and it is always present as an option, but our job is to choose another way.

In the relational work of teaching, and teaching writing in particular, the “Why are you helping me?” or “Leave me alone” moments make me realize the gravity of teaching and the importance of students re-visioning themselves through the act of telling their stories. With my student who was writing his book, I worked to redirect the “quitting before failing” learning pattern, so that he could learn to push through the productive failure and change his response to his frustration level.

Teaching is coaching in a learning environment that lifts up productive failure.

Coaches don’t assume their players will fail. They push them to get better, but they don’t say, “yeah, I’m done with you.” There’s a contract or understanding based on the value of the player. As a teacher, I am constantly reframing from that same coaching perspective—always keeping the asset-based mindset. Failing forward is a choice, both on my part as the teacher and the part of my students. And no one is going to fail without a safety net. Building students’ metacognitive skills within a restorative approach helps students to understand how to use failure and increases learning outcomes. The persistent redirection of “No, You’re not done; there’s more to do; let’s figure it out” is an acknowledgement of a student’s humanity, offering the space to grow. This restorative redirection is also an acknowledgement of the high rigor and standards we believe a student will meet.

On the twentieth day of my student’s writing I printed 30 pages and bound it with a large clip. When I showed him, he stared at the cover page without saying anything, then slowly flipped through each chapter. “I did this?,” he asked. And then he sat down with a pencil in hand and started to read his own story.

Three months after summer school, I presented at our school’s summer training for staff. I asked my student if I could share a paragraph of his memoir with the staff to help people understand firsthand a student’s self-perception as a result of experiencing persistent failure in school. The last slide of the training was just one paragraph of my student’s writing. I presented it as a reflection moment. Soon after, another adult asked to read his memoir. And then another. From time to time my student will text, asking for a book title or sharing and idea for a story. Being a part of this process is transformative.

I am experimenting with how to facilitate failure so that it holds new meaning in the learning process. When the student hits a wall and quits, I now resist the temptation to help or guide as readily as I have in the past. I push with a restorative lens, providing consistency and unconditional promise that students are not yet finished with a learning process that requires them to dig in and find their own way through. That is the meaning I have made with “productive failure.” It’s a mindset shift for me as a teacher, one that I learned from teaching students who “didn’t write” and “didn’t read”…until they did.