Two years ago, and two months into the start of another year of Zoom learning, like many of us teacher folk, I hit a wall. I had only heard six students speak. I didn’t know what my students looked like apart from the avatar on a blank screen. While this isn’t unique to my teaching journey in Zoomland, it is the catalyst for my personal moment of “Okay, this isn’t working, so now what?”

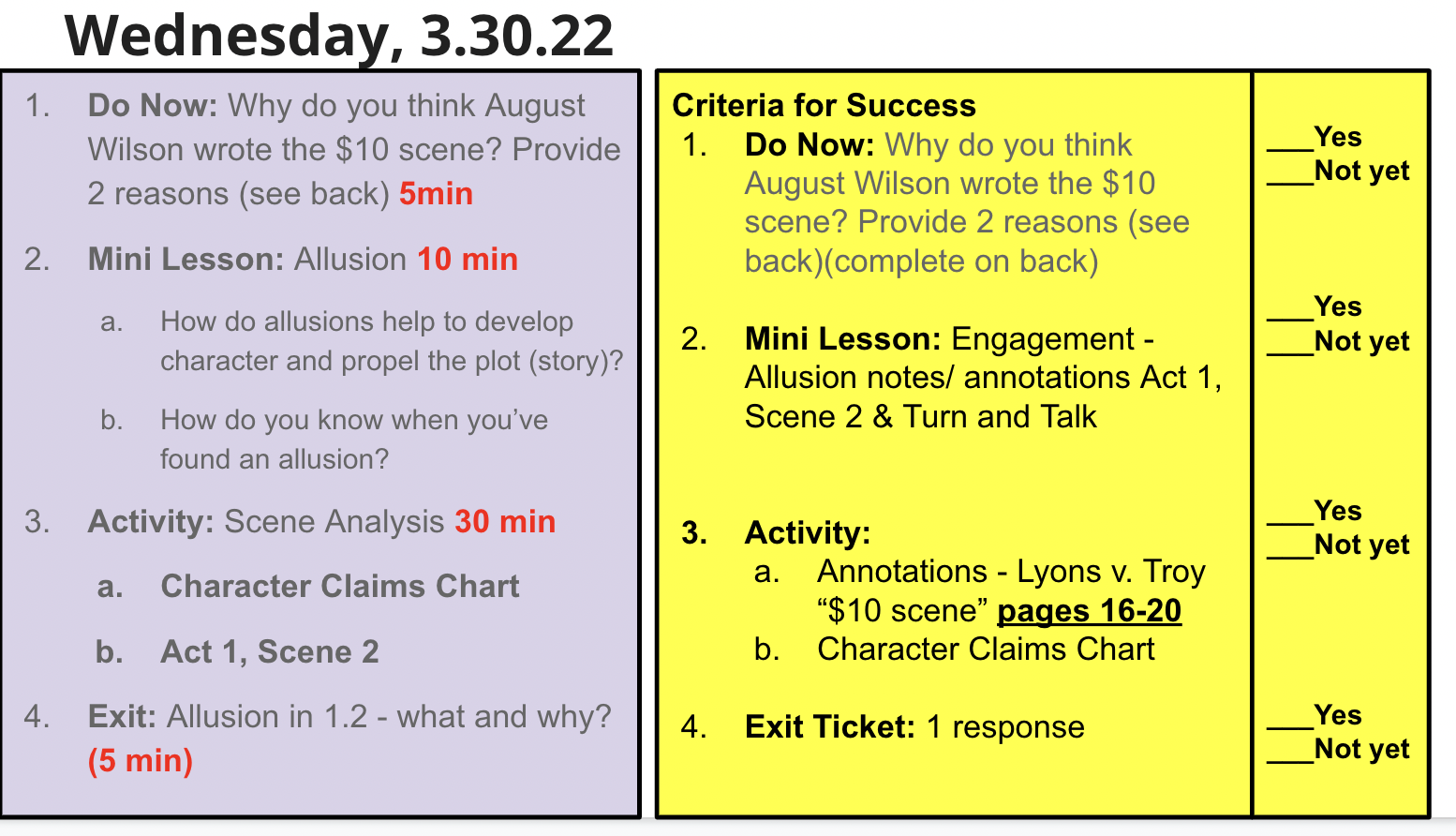

Zoom or no Zoom, my school’s instructional focus still called for instructional dialogue in every class. Certainly a full believer in instructional dialogue, I still struggled to replicate the practice on Zoom. The feedback I received after my evaluator observed an AP Language Zoom lesson was to work on leveraging more student voice. I didn’t see how that was possible on Zoom at that time, but I would understand it months later when I took the leap into digital debates. My mind could not digest the act of “doing a debate” on Zoom–especially when students were not talking either in breakout rooms or in whole-class “discussions.” I knew how to do in-person debates, but the alternative felt impossible.

Here’s how it went down

“C’mon just say something.” (YES! Someone unmuted! I’m literally clapping.)

Then, in the chat: “Cloudy. Cloudy. Cloudy. Stormy. Cloudy. Hurricane. Yeah, pretty windy here. IDK, TBH IDC. Maybe sunny?”

I don’t think I was the lone teacher who started Zoom class with the question, “What’s your weather (mood/feeling) today?”–a faux “circle” opener as social-emotional check-in. I held tight to the belief that ritual and routine helped students normalize the Zoom classroom.

So I was facing this wall of “So, now what?” and could not turn away from that pokey question. I felt the urgency to design lessons that held a deeper meaning and that matched the importance of our critical consciousness emergent of the Twin Pandemics: Racial reckoning + Covid. I felt passionately about the urgency required within my capacity as a teacher to do something with whatever tools I had to teach with at that time. I remember sitting in my kitchen, my dog panting next to me, staring at the Zoom screen with blank squares, and saying something like this (what I thought to myself every single day of teaching with my dog from my kitchen):

“This is the time. You are living this moment for the first time. We all are. Your experiences right now will be read and talked about by your grandchildren. We have never been here before.”

I went on for too long. Or, maybe not…I had no social cues to read. But I said this repeatedly with different words on different days. I felt it in my core. This time was an opportunity; no, not opportunity, obligation. I either choose to engage in this moment as an educator or keep it moving (in the other direction…backwards).

Making a choice is taking a stance in every lesson

I chose (and will always choose) the obligation=opportunity route. But my passion, intention, and sheer will were not producing results. Students were not just disengaged, I’m not sure they were actually present. (Side note: Fast-forward two years, and my Zoom 10th graders are now my seniors. They laugh about the Zoom Year and how much freedom they had to disengage if they chose to mute and sleep or mute and FaceTime or mute and…[fill in the blank].)

But then…Algorithmic Bias, Justice & The Poet of Code

The lessons I taught in the “before times” lost relevance and impact in 2020 Zoomlife. I had to do it differently. Something clicked for me when I listened to Manoush Zomorodi’s interview with Joy Buolamwini on NPR’s Ted Radio Hour. And this question (also the segment’s title): How Do Biased Algorithms Damage Marginalized Communities? opened a door to a new opportunity. Algorithmic Bias. I asked my students the next day, “What do you think of when you hear ‘Algorithmic Bias'”? And this time, their silence was a signal to me to ask differently. So I asked it like this instead: “What if you heard those two words apart from each other, like ‘Where have you heard the word algorithm before?’ and ‘Where have you heard the word bias?'” Their responses back to me in the chat were more than one-word answers for the first time since we started in September (and it was November). We then had a discussion between chat and actual talking about the impact of putting those two different words together– with two different contextualized meanings –to create a new meaning. This was a big learning moment for me, and I hope for my students.

Obligation & Opportunity in Action

Based on critical consciousness of systemic racism we are obligated as a society to re-contextualize our lived language–in this case the joining of the two words “algorithm” and “bias.” My students had not thought of bias as related to algorithms, but once they listened to Joy Buolamwini’s Ted Talk (How I’m Fighting Bias in Algorithms) and then her interview with Manoush Zamorodi, they not only understood the implications of algorithmic bias but pushed each other in a debate for the need for algorithmic justice. My students’ excitement that there is the option in life to be called a “Poet of Code” was matched by their exposure to Joy Buolamwini’s story: If she can simultaneously fight racism, and fight the algorithms that design and perpetuate an ingrained cultural bias, then so could they.

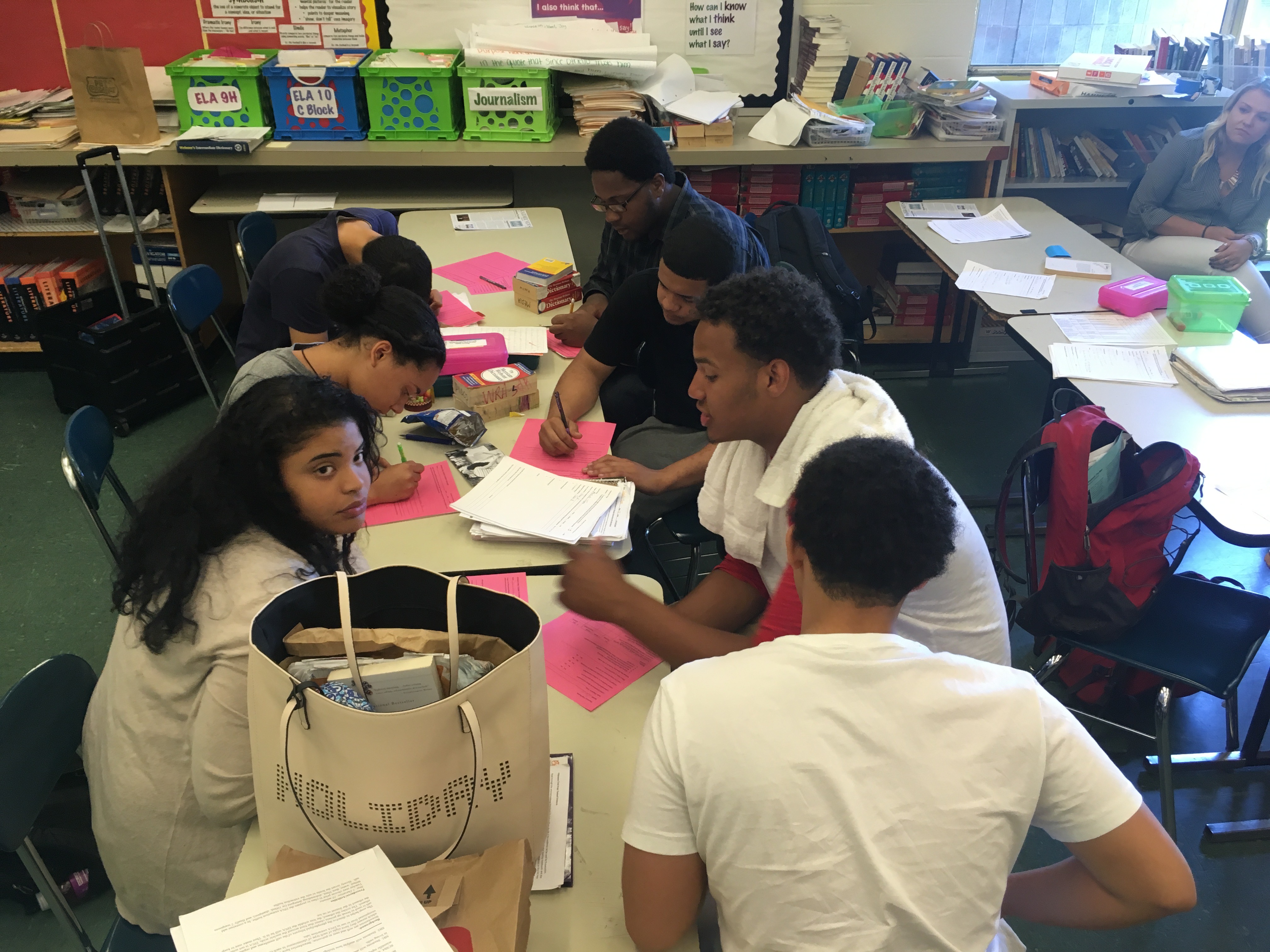

Through discussion that eventually led to a formal debate (YES, on Zoom!), my students recognized the fight in something so seemingly benign as an algorithm. The irony here was that we were doing this work within and among AI culture. My students (now as seniors who admit that social media became their only social structure in 2020 Zoomland) began to question the flipside to AI and social media in their lives:“Wait, you mean what you see on your ads are not the same as mine?” I shared ads that popped up in my social feed: lipstick for “mature” women and area rugs on Wayfair. They laughed, but then compared the ads they saw and dug deeper to question economic justice behind those ads.

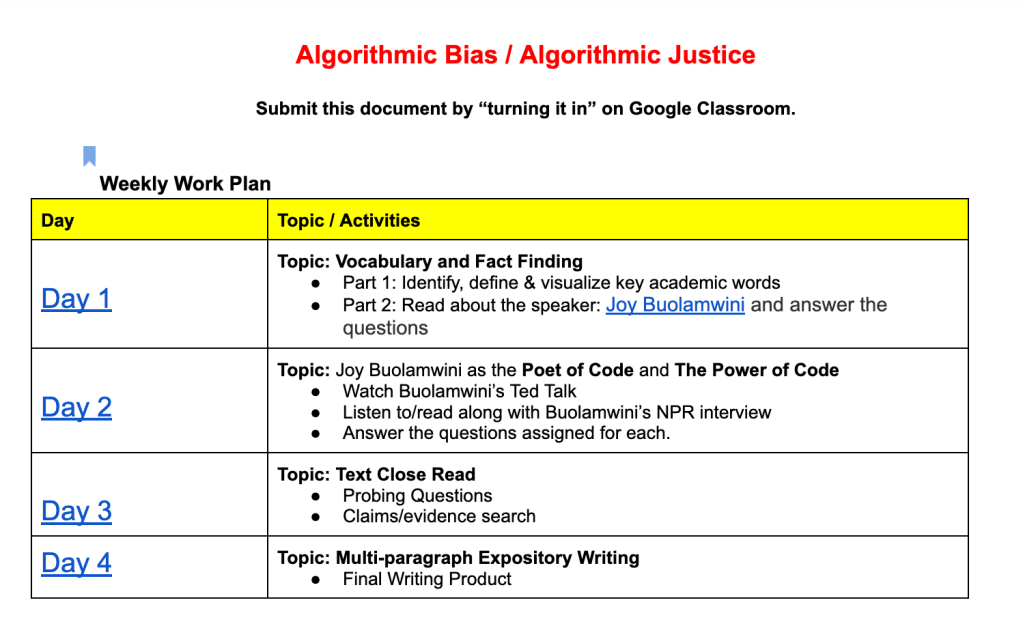

We Zoomed through this AI discovery together. Over a four-day lesson, and then a full debate, my students were ready to write a letter/email/article advocating for Algorithmic Justice. While some writers focused on social media and advertising, the majority of writers shared concern for racial profiling and systemic racism due to algorithmic bias.

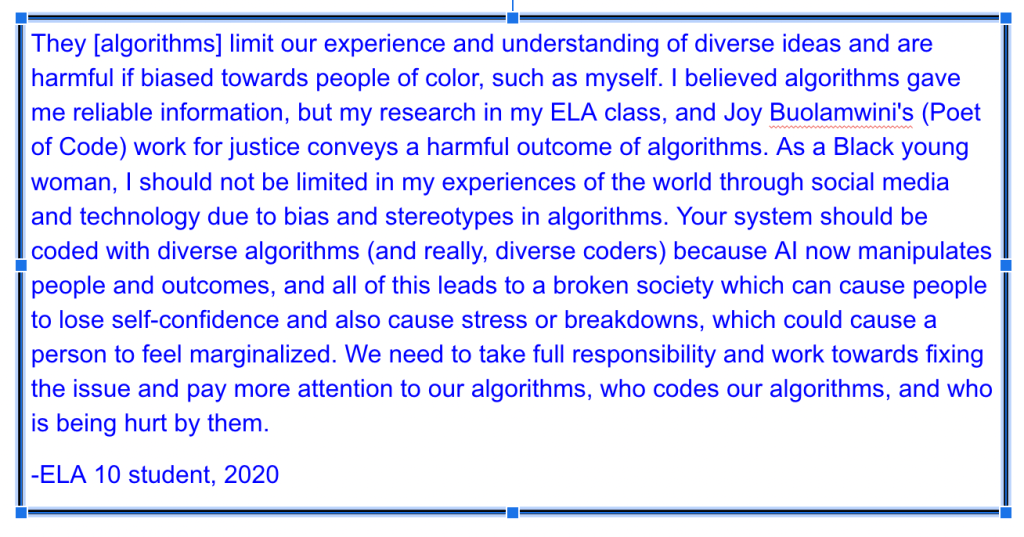

One student shared the urgency of algorithmic justice like this:

What we’re experiencing now with bias in how algorithms are being written is like a fire alarm being pulled and no one coming to put the fire out. And the fire is literally burning some people and not others. Who’s going to put this fire out? I’m not sure it can be put out if not everyone sees it burning.

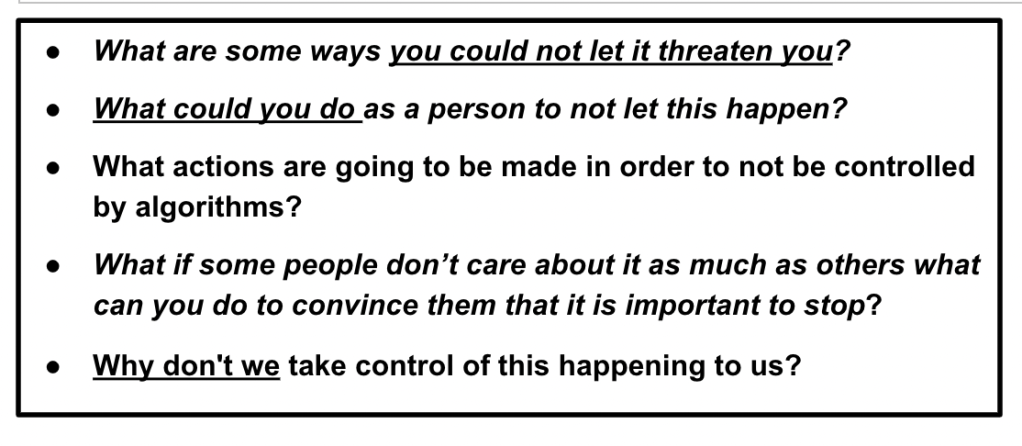

The debate prompt was challenging — a great opportunity for productive struggle through unpacking the prompt, writing about it, and then interrogating it with questions in their debate teams. Students who wanted more of a challenge opted for the “Con” side of this prompt, pushing themselves to argue the opposite of their own opinion, as I reminded them, they will do when they become lawyers. A good reminder that we debate positions, not opinions. (Check out more resources on debate for middle school, high school beginners/English Learners and a sample Debate structure for AP Language).

Students pulled apart and interrogated the debate prompt:

Another student wrote an email to Apple (excerpted below) for her advocacy writing, one of the steps in our Algorithmic Justice mini unit.

The catalyst for my change as a teacher–honoring the obligation and opportunity in each teaching moment–was hitting that Zoomlife wall of disengagement and pushing myself to question alternatives to what I had done before. The topic of Algorithmic Bias/Justice was a game changer for my students as it brought out their authentic questioning, as they grappled with concepts they had never encountered, and pushed each other by using evidence in debate. And, they got to know Joy Buolamwini, The Poet of Code, realizing that such a title and purpose exists.

I created the four-day mini unit and debate at a time when I new something had to change but had little time to make that change happen. It’s a starting point to understanding AI Justice and provided space for students to engage around a topic that they are still talking about two years later.

What now?

This December 20, 2022 Twitter post from The Algorithmic Justice League (@AJLUnited) calling for equitable

and accountable AI caught my attention just this week. What can I do as an English teacher to give space for AI justice in my classroom? I can’t help but admit that I missed an opportunity — am missing an opportunity as I write this– to do better with AI justice through action research writing, and further, through cross-curricular project-based learning. I can say that it is because my school does not have resources (time, staff, school design) to do cross-curricular work, or to take a side-step from mandated curriculum and testing to give students the chance to explore this issue. But, then, I reflect the obligation and opportunity on my part. The question I am grappling with for myself is: How can I break that proverbial wall and do this work in my classroom at a deeper level beyond what I could do/did on Zoom…with or without resources to support that work?

But, here’s the missed opportunity, and one that I hope to build in the future:

What if we were able to break the walls between disciplines and align ELA, Math, Science, Art, Business, and History to engage students in action research and problem solving through design challenges? Importantly, teachers need to have time and space to plan for cross-curricular impact. As I think about full circles (2020-2023) and reflect on how far my students have come in two years despite Zoom, I also think about my role as an educator to not just “Keep it Moving” but to stop and honor the obligation and opportunity to make learning about AI Justice a thing we do. The “wall” will always be there for an under-resourced school like mine, but so will that intentional teacher choice to do something different for students who deserve to know they can be a Poet of Code if they want to be.

#AIJustice #AIHarm #AIBias #ELATeacher #ActionLearning