Dr. King’s “What Is Your Life Blueprint” speech gives a different perspective to King’s rhetoric. My students are immediately pulled in to his message when they watch him deliver the speech to middle school students. His words, supported with vivid images and strong metaphors, speak directly to students.

With the mission of getting Dr. King’s words off the page, I transformed the way I taught the rhetorical situation through this speech. Each activity centers student voice and agency in Dr. King’s message of finding and sticking to your life’s path no matter what obstacles stood in your way.

Tableau or Spoken Word Performance

Tableau and spoken word performance is the ultimate engager as students to physicalize with feeling Dr. King’s rhetoric. This trio created the image of the “crystal stair” in the speech and gave a passionate, from-the-heart mini performance. With just a small bit of text, and in under 1 minute, students can focus in on one or two images to create either a still picture in a tableau or a performed mini scene, putting voice to text. Students feel the alliteration, repetition, and rhythm in a way that cannot be replicated by silent reading.

Discourse Builder Roundtable Discussion

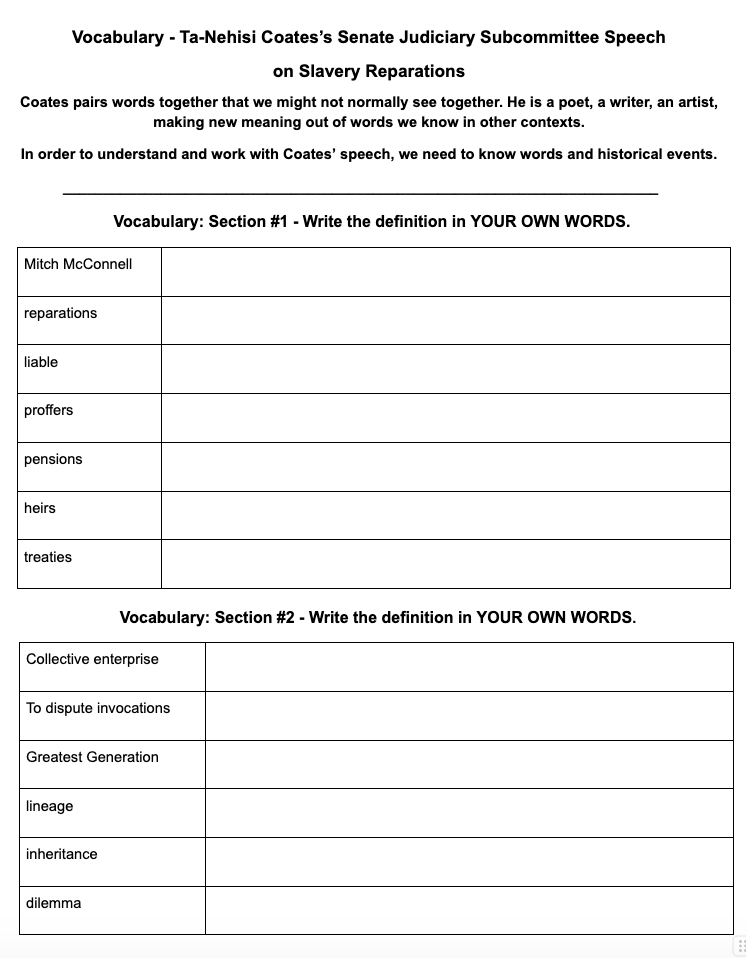

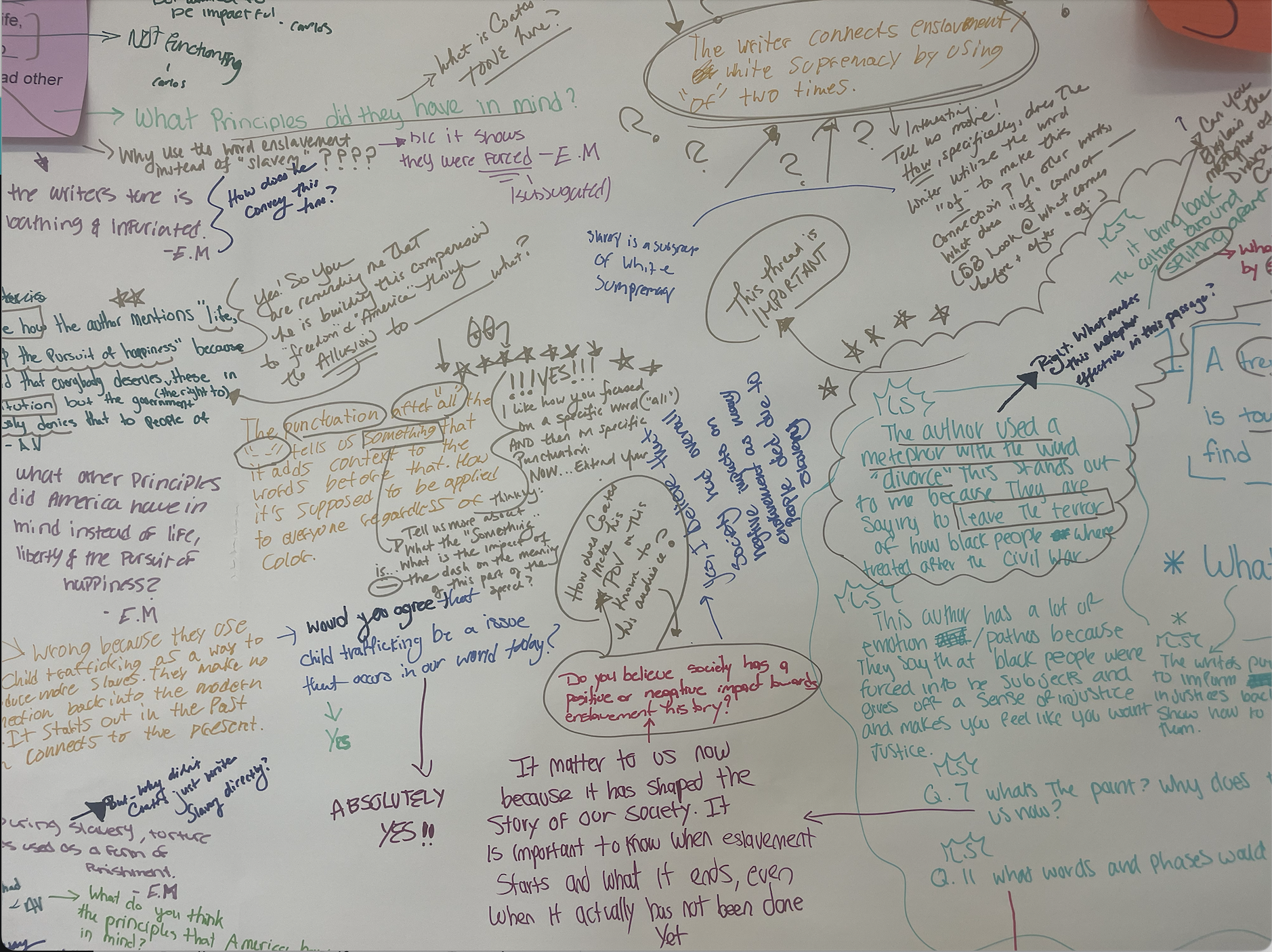

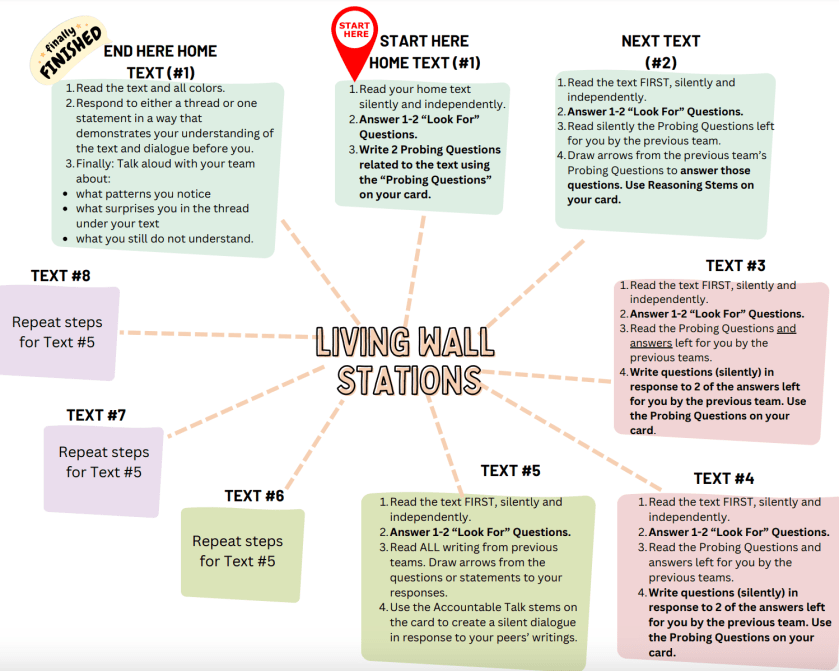

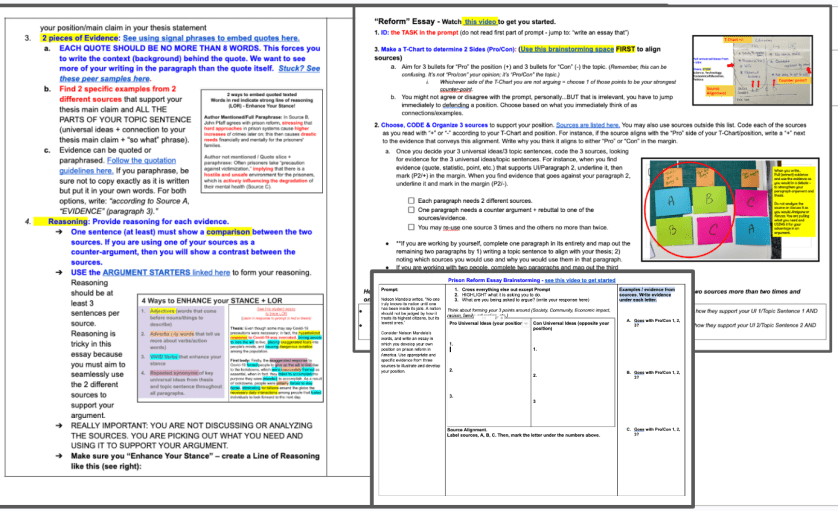

What it is: Join 4-5 students together to practice accountable talk and close reading. This is called a “discourse builder” because students are tasked with using probing questions to add on to what each person offers in discussion. This discussion focuses on close reading. Each student receives a text selection from the speech as a “mystery text.” I call it a mystery text to build anticipation before we read.

Why it works: Student voices are central to this activity just as student agency. They are not only engaged in discussion with each other, but each person gets to lead the discussion for their specific text selection. This builds excitement and serves as a scaffold to reading the full speech as students have already chunked and analyzed language in their “mystery text” slices. At the end of this activity, they have made and shared personal text connections, built community through shared ideas, questioned the text, and are familiar with unknown words, writing style, and message. And all before we even read!

The strategy:

Step 1: I select 4-5 chunks of text, focusing on excerpts with a significant amount of unknown vocabulary, complex sentence structure, imagery and metaphor that connect back to Dr. King’s message. I also make sure to differentiate text so that some selections are more easily accessible. I like taking selections from beginning, middle, and end of the text so that students get a sense of the arc of the speech before they read and can say “I know this!” when we get to the full text.

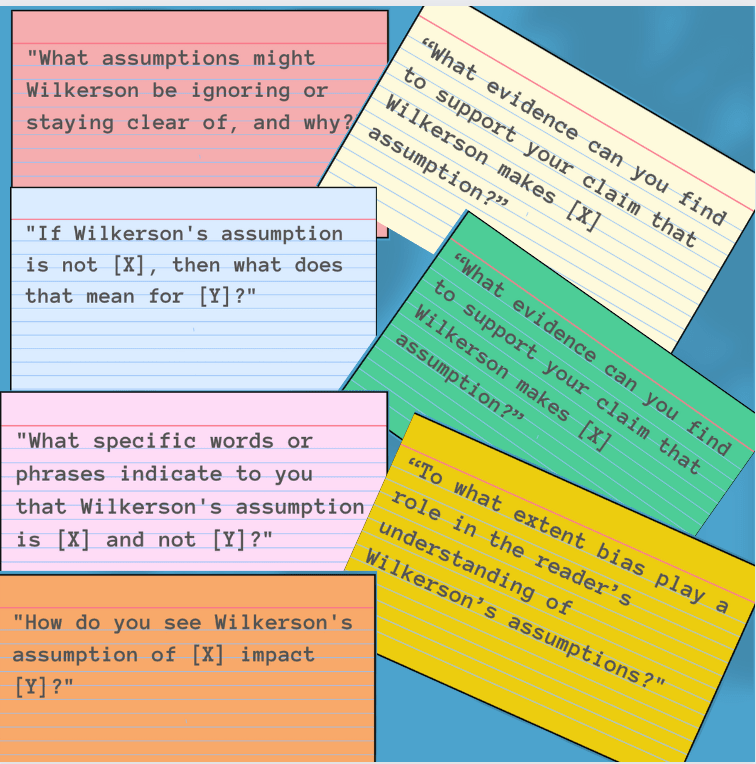

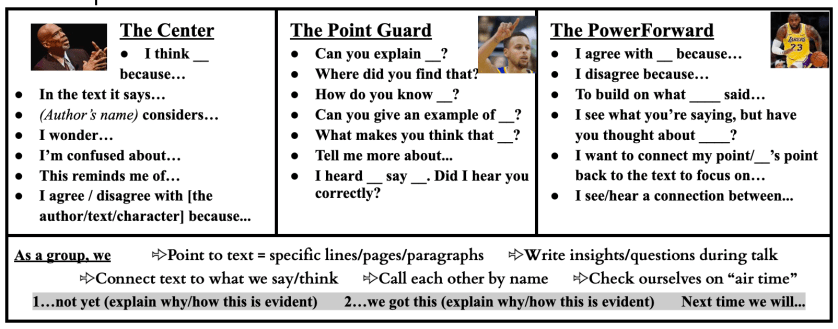

Tip: Point students in the direction of probing questions to focus and redirect accountable talk moves. I have on hand laminated probing questions cards. For my tenth graders, I love the “basketball question cards” that divide probing questions for accountable talk into three roles: Point Guard, Power Forward, and The Center. Students can’t miss these bright green cards in the center of the discussion.

Step 2: Cut up the text selections, making a set for each student group. Each group receives a “Discourse Builder” handout (linked here for free) with boxes for each text selection. I love manipulatives and any opportunity for hands-on engagement. Students glue in each text selection as they work through the activity. Each student is responsible for one of the text slices. They read their slice independently, making personal connections and questioning the text. In a round table discussion, when it is time to lead, each student shares their connection and questions to the table and leads a discussion about their text slice using probing questions.

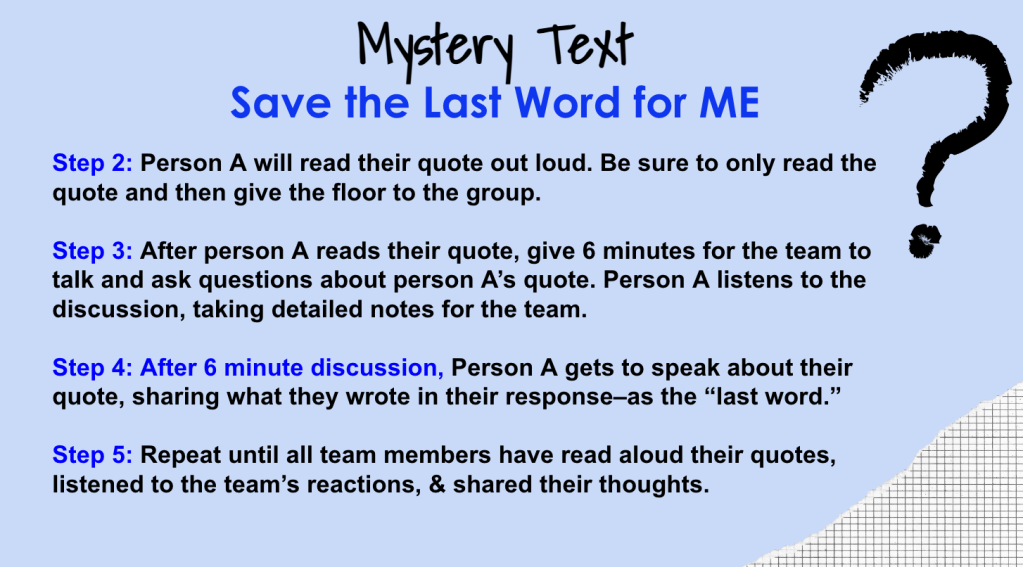

Save the Last Word for Me

What it is: Similar to the Discourse Builder Roundtable, Save the Last Me provides opportunity for accountable talk with a focus on listening to learn. This is a great replacement option to the Discourse Roundtable if you are using it as a pre-reading activator with “Mystery Text” quotes. It also allows students to zone in on specific parts of the text during reading and as a reflective exercise looking back on the entire text post-read.

Why It Works: This is great for students who don’t like going first as it allows time for processing — the initial first step as the discourse leader is to read the quote and then step back and take notes to capture what the groups says in response. I love this strategy for building strong listening. It’s also a helpful exercise for students who struggle to monitor air time in discussion as it provides a structure for holding back to let other speak.

3 Levels of Text Discussion

This is another great discussion framework that facilitates text-to-self and text analysis through close reading. Read more about how to do this in your classroom here. The resource can be found here.

Reflective Writing Responses

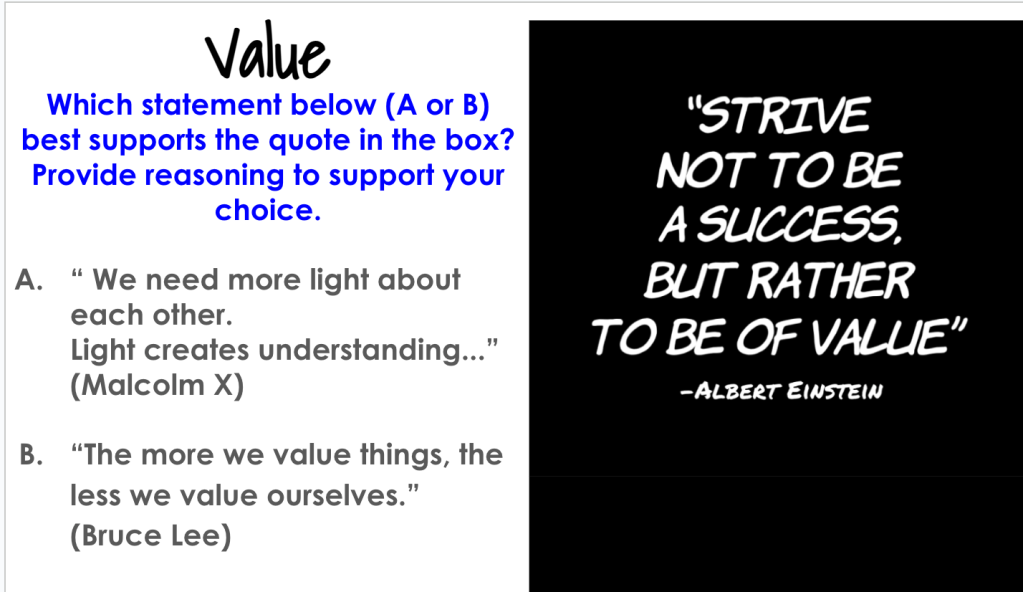

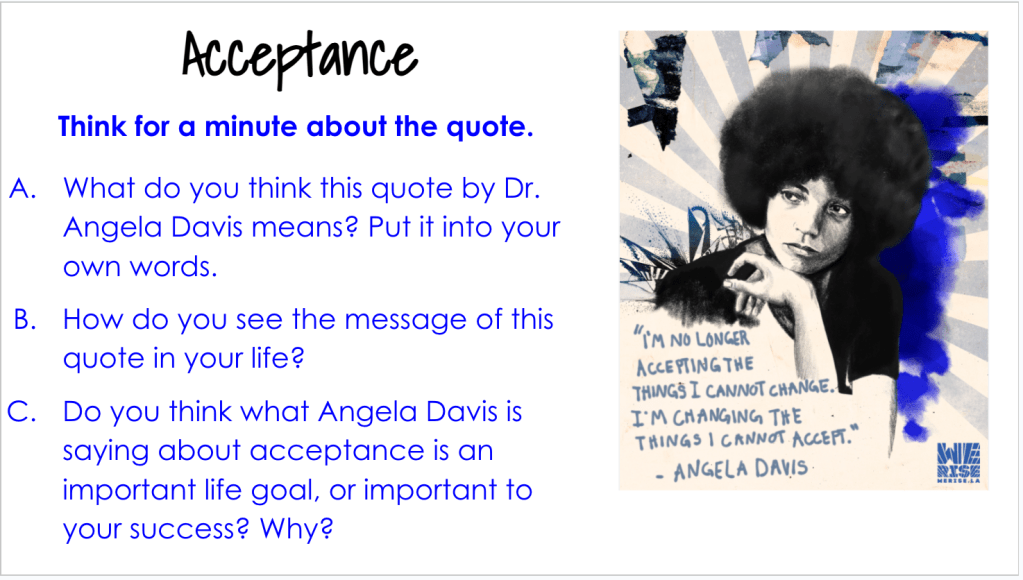

What it is: Sometimes I call this “meditation” writing. Getting students to think about their thinking, building metacognition in reflective writing, also builds writing stamina as students learn to flex their reflective muscles. While my students read Blueprint, I integrate quotes relating to Dr. King’s message in the speech focusing on success, failure, adversity, tenacity, etc. from Audre Lorde, Angela Davis, Malcolm X, to name a few.

Why it works: These prompts are great discussion points on their own and create a nice compare/contrast analysis with Blueprint. The prompts work well because of universal themes, but also because they push students to compare and contrast–and synthesize–ideas from different voices. Here’s a few from my slide deck below. The full slide deck with 11 prompts can be found here.

Close Read with Purpose

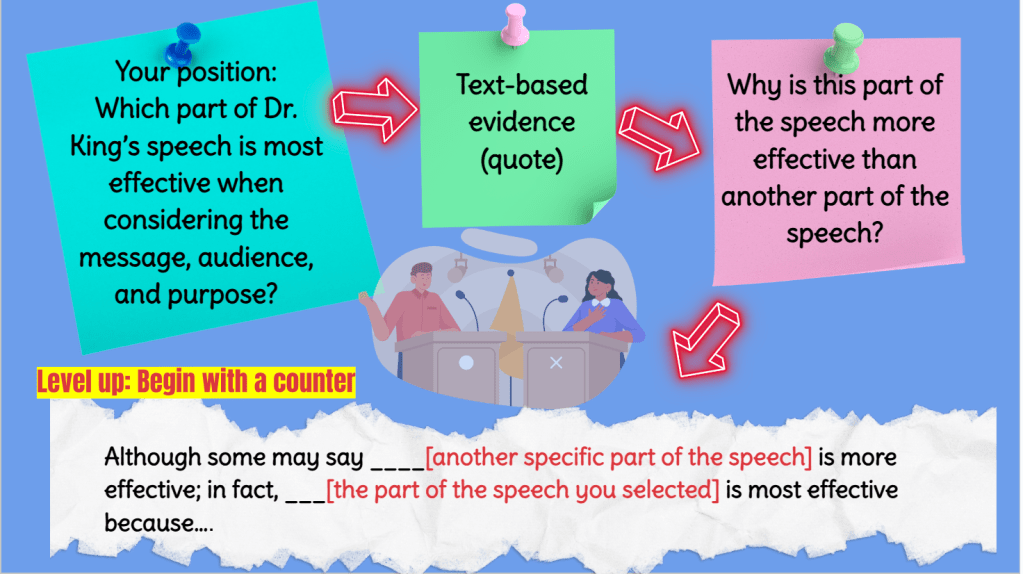

What It Is: Before they read, I tell them that their reading mission is to determine which part of the speech (chunk 1, 2, or 3) is the most effective given Dr. King’s message and audience. This becomes the question for a debate or socratic seminar post-reading.

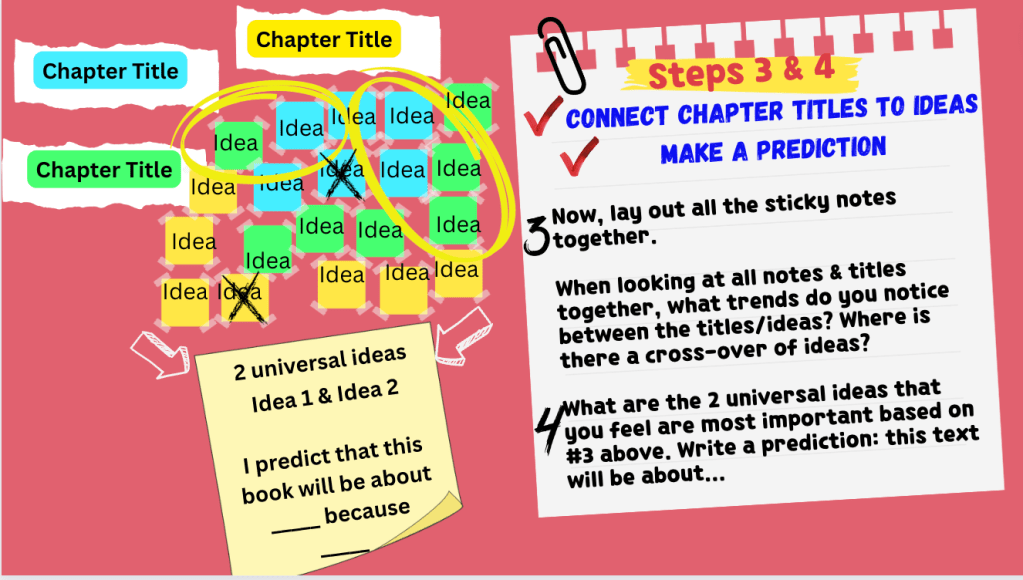

It’s important for students to learn to read for message (what the writer wants) and understand the relationship between message and audience/reader impact. After the pre-reading activator Mystery Quote activity, I introduce the concept of message and audience through the lens of universal ideas. It’s important for students to base their reading or analysis in universal ideas rather than facts or evidence. It helps students move from “What happened” to “So What” about what happened. Check out my free Universal Ideas lesson here. As a tenth grade, Pre-AP and AP Language teacher, universal ideas are the groundwork for analysis and prevent reliance on plot summary.

Why It Works: My reading go to is Reciprocal Teaching Groups, or variations of RTGs, where students read collaboratively to build meaning. In collaborative reading groups, students either work with Task Cards or with specific reading look for’s. This mission-focused reading sets up close reading with purpose and helps students to self-manage the text. Collaborative reading helps students process multiple look for’s simultaneously and pushes students to build stamina with a multi-step reading process. I have found that students are less likely to give up if they have a role to fulfill and are accountable to a reading group.

How: I have a digital version of Blueprint that is color-coded by three sections (beginning, middle, and end). It includes guided reading questions in a format that visually separates text for readers who learn better with sight markers to break apart the text. Color coding, or breaking the text into distinct parts, chunks the text with purpose. For paper people (I’m still in that bunch), a non-color copy is numbered into three sections, and students can box-out each section in different colors to visually code the text before they read.

Blueprint is rich in metaphor and imagery. A good starting point would be to talk about the title, connecting “blueprint” with the reflective writing prompt themes or messages, metaphors, and imagery that stood out to them from their Mystery Quote pre-reading activator.

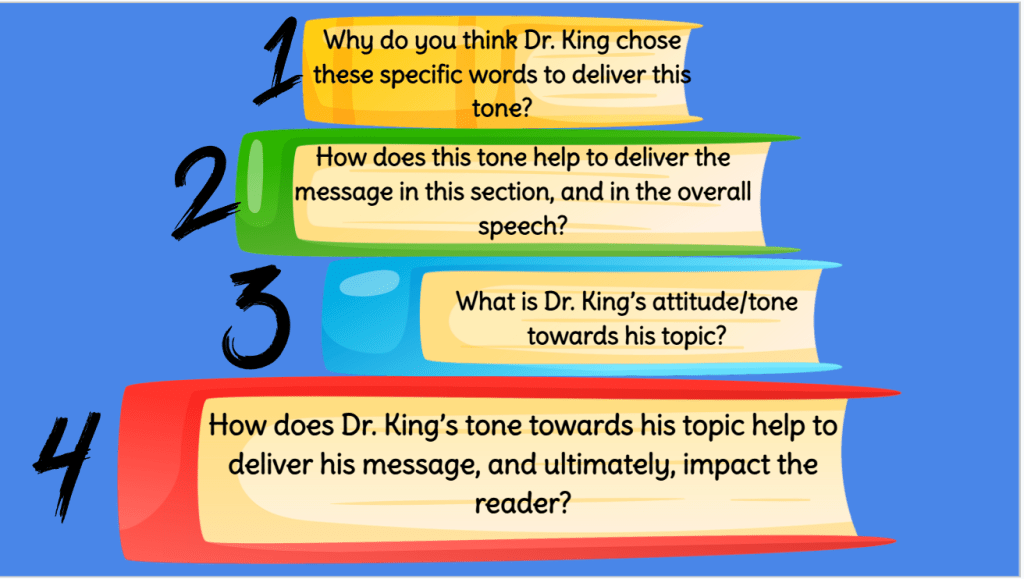

This speech is a great way to introduce or reinforce the idea of tone as the author/speaker’s attitude towards their subject or topic. I find that students can easily spot tone when reading fiction and analyzing a character’s tone, but with speech analysis, students are learning to “read like a writer” rather than their life-long habit of “reading like a reader.” It’s really a flipswitch moment for a lot of students. This free “SPACECAT” resource is a great tool for rhetorical analysis. This “Read Like a Writer” lesson on diction and tone is also a good next step in rhetorical analysis. Check out my bundle of “Read Like a Writer” resources.

Here are some questions about tone and message to guide reading like a writer:

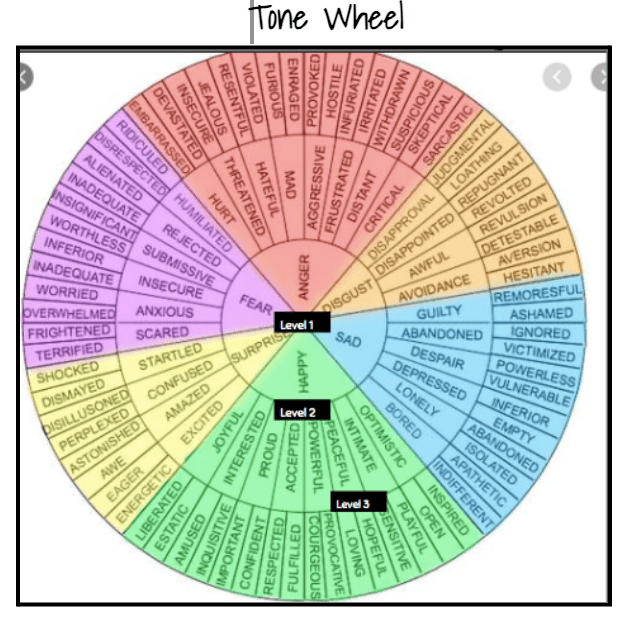

A tone wheel (honestly, I would wear this tone wheel every day–that’s how much I use this in writing and reading) is linked in the reading and helps students attach Dr. King’s language choices to tone. It also sets up a nice follow-up question for students to dig in deeper.

Synthesize Ideas with Socratic Seminar or Debate

Students take their reading purpose question and prepare a position statement or response for seminar or debate.

Level up debate through these moves:

- Give students a position to defend. Students may at first question how they will debate a part of the speech, but building their argument muscle can begin with framing the parts of King’s speech as being defensible.

- Adding in the “message and audience” as parameters can raise the cognitive demand as students must apply their knowledge of both to build a case for the part of his speech that is “most effective.”

- The demand is increased even more when students push their argument to include how their selected text is more important than the other parts of his speech.

Check out more debate resources here.

This debate question can also apply to a Socratic Seminar discussion as students prepare text to support their position on the prompt. I’ve designed Seminar pre-work for students to verbally share their thinking with a partner before writing independently to prepare for the group Seminar.

Blueprint Lifts up Student Voice

This speech empowers students to connect to Dr. King’s message. The structure outlined above engages students even before they read the entire speech as each student leads discussion of a part of the text and makes it their own. It’s powerful to watch students enter the world of this speech and without even knowing it, they have learned the rhetorical situation through student-led discussion, close reading for metaphor and tone, and defending parts of the text against a claim in debate or socratic seminar.

I’ll end with a student’s observation of his “Mystery Text” selection during the Discussion Builder Round Table:

“If you are going to be at the top of the game, or at the bottom. Whatever you’re doing, going up a hill, playing ball, swimming, whatever you got to do…You’re going to mediocre it or be at the bottom? You might as well just do it. When he says “scrub,” if you think about it…what could that relate to? Scrub is like negativity. I relate that to basketball. When you call somebody a scrub in basketball, you’re being disrespectful. But he said, ‘be the best scrub,’ so he’s saying even if you’re down and not doing good, give it your best. That’s what I do. I can relate to that.”

Resources in this article:

Dr. King’s Blueprint Speech full resource, including:

- The Discussion Builder Roundtable (digital and print versions)

- Save the Last Word for Me (+ colorful quote cards, writing space, exit ticket, and slides)

- 11 reflective writing prompt slides

- Dr. King’s Blueprint speech with 3 sections divided by color, guided reading questions, and links; Blueprint speech without color for printing, also with guided reading questions and separated into 3 sections with numbers.

- Debate slides pictured above

- Colorful tone wheel pictured above

- Socratic Seminar pre-writing space + partner share cards

- Socratic Seminar accountable talk tracker and individual reflection space

Basketball Accountable Talk Cards / Probing Questions

“Read Like a Writer” lesson on diction and tone

bundle of “Read Like a Writer” resources