In my search for complex, culturally relevant text, Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste is at the top of my list. Caste serves as a mentor text to elicit, entice, and engage my AP Language students from Argument to Synthesis. Students engage with Wilkerson’s multi-layered thesis to fuse examples from her text, along with other sources, as evidence to support a their argument about prison reform. The steps I share below outline how I design lessons with complex texts such as Caste to deliver on equitable literacy, culturally relevant teaching, and cognitive demand.

Step 1: Start by slicing the text…

I’m a believer in depth over breadth. And when thinking about facilitating access to complex texts, I “Zoom in to Zoom out.” Start small, and choose an excerpt that your students can digest with the purpose of gaining comfort and confidence with Wilkerson’s complexity, recognizing that complexity is seeded at the word level, rooting outward to sentence, paragraph, part, and whole–the universal ideas that build themes. So, with those concentric circles in mind (and I’m literally picturing the circles in a tree trunk: the word-level complexity is at the very tiny center circle, and the conceptual, big-picture-conversational-takeaway-ideas are at the very outer circle.) So, for the first read (the read that elicits and entices), decide if you want to narrow in on a one page excerpt or 5 pages. Wilkerson’s text is high complexity and lexile, so I plant the seed with a 3-4 page “slice.” I often don’t pull from the beginning; instead, I go for a slice that alludes to those thematic takeaway ideas that we will need as a jumping off point for our Synthesis “Prison Reform Essay.” But, I will have students return to a larger excerpt after the Step 3, below, so that they can analyze lines of reasoning in Wilkerson’s arguments beyond the slice.

Step 2: Decode the Slice for Vocabulary Pre-Read Peer Teach

I’m not a believer that students need to know every single unknown word in order to understand a text. However, pre-reading word work is important and makes a difference for our Step 3 activity. Here’s how I do it with the initial slice of text:

- Select key words throughout the excerpt, focusing on words or phrasing that serve your intended reading purpose AND skill for Caste in your classroom. I do a mix of tier 1, everyday words and tier 2 words that are more academic. Within this list, I make sure to include words that are specific to our purpose for using Caste, and these are concepts related to our Synthesis Prison Reform Essay.

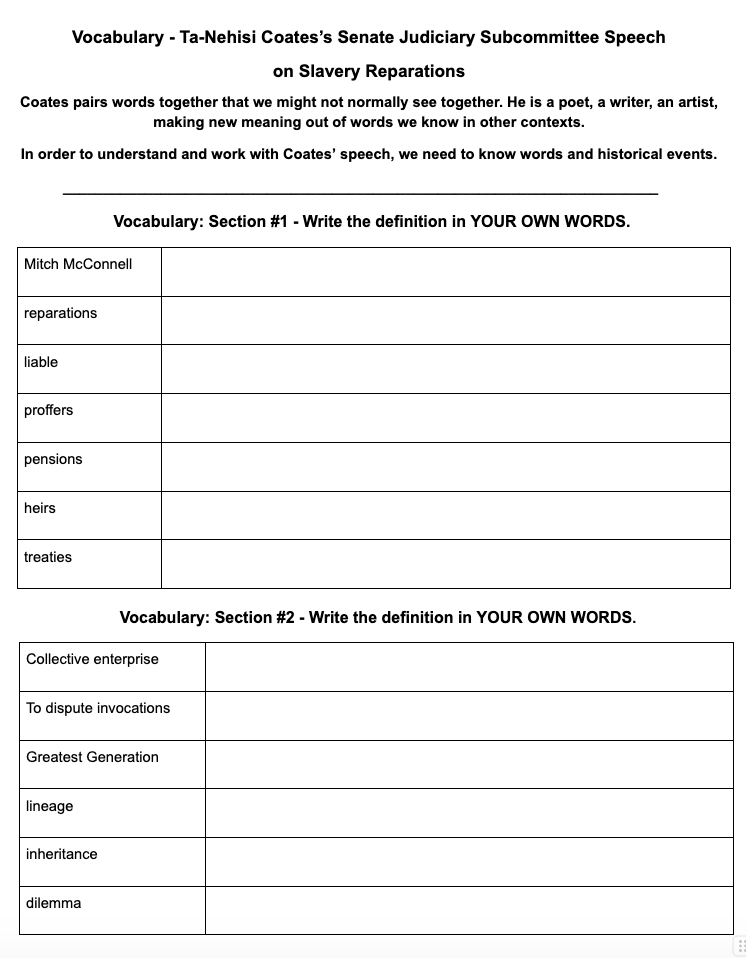

2. Organize the focus words in a basic graphic organizer (see right) with enough space for students will write definitions in their own words in a peer-teach activity. This is an example of this from another complex text, Ta-Nehisi Coates’s speech to the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee for Slavery Reparations.

I divide the focus slice of text into 5-6 chunks. I am only aiming for 7-10 words/phrases per each chunk.

3. Get students into groups – each group is responsible for making meaning of their words/phrases in their own words – you can do this with a Frayer model template, but I had students use chart paper (see right). You can definitely get more creative than I did; next time I might have students pair their word posters with found objects that represent the idea/concept of their word to help bring their posters to life. This exercise, for me, was not about the art of presentation, but about students getting to the understanding stage of the word by defining, identifying connotation, and then conceptualizing. These word posters are displayed prominently for students to access not just in our work with Wilkerson’s text, but also for our Prison Reform Synthesis Essay (coming shortly!)

4. It’s Vocabulary Peer Teach Time! Students engage in a Gallery Walk, and with each poster, they captured definitions/pictures on their vocabulary graphic organizer (see #3). Another option is a Jigsaw peer teach strategy or stations.

Step 3: Getting into the Text: A “Living Wall” Silent Dialogue

Now is time for hands-on text engagement with the specific excerpt that serves your reading purpose and skill. My reading purpose was to:

Set up and scaffold the cognitive lift of synthesizing source material into an argument essay where students take a position on prison reform.

Engage students in complex text and multiple, equitable strategies for reading comprehension, so that students understand how to navigate text critically (evaluate and synthesize) with an argument lens.

“Living Wall” Step 1: Prepare the Text Selection

Look for either consecutive pages of text or short sections excerpted across a chapter or even the entire book. I took six sections excerpted across the entire book that illustrated underlying universal ideas that I wanted students to identify and work with in our Prison Reform Essay. So, I looked for sections that contained data-rich evidence, story-rich anecdotes, along with implicit or explicit references to universal ideas like “inequity,” “hierarchy,” “disillusionment,” “stigma” and “otherness” (grab a free universal ideas resource here.) I was especially interested in Wilkerson’s idea of “scapegoating” (190-201, 234) as a baseline concept that would be a jumping-off point for my students to generate idea-based impacts of prison reform. Think about taking excerpts that illustrate or expose implicit universal ideas rather than those “right there” ideas that are named on the page. This will set up analytical thinking, which is important when students are ready to write arguments as the arguments need to be organized around ideas, not examples. I typed each excerpt in large print, splitting them across 10 different pages.

Text selection and Cognitive Demand

What makes working with Caste for evidence in support of arguments on prison reform so challenging is that Caste is not explicitly about incarceration. Students must rise to the challenge of digging below the surface to extract the universal ideas embedded within the text to determine how those ideas can be applied to an argument about prison reform. Wilkerson’s idea of “Scapegoating” is an example of this cognitively demanding task as students grapple with how Wilkerson’s thesis of a “Scapegoat caste” serves their prison reform argument (Caste, page 191).

“Living Wall” Step 2: Prepare the Space

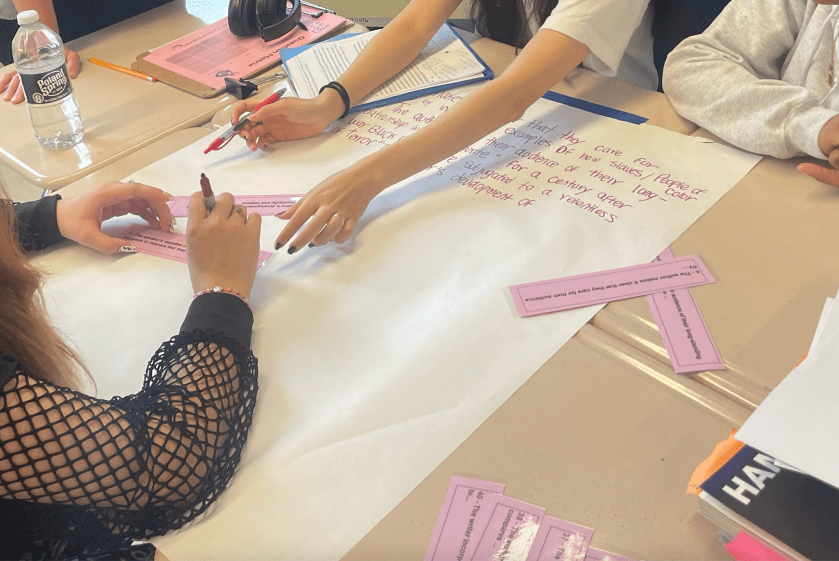

The Living Wall is a visual engagement tool, making the process of close reading visible for peer observation, questions, and connections. I call it “The Living Wall,” but I did not create this strategy. It’s an iteration of “Big Paper,” which is described best by Facing History and Ourselves–a great resource for high engagement activities.

Creating the Living Wall

Tape up a roll of paper to create a continuous blank canvas for student work.

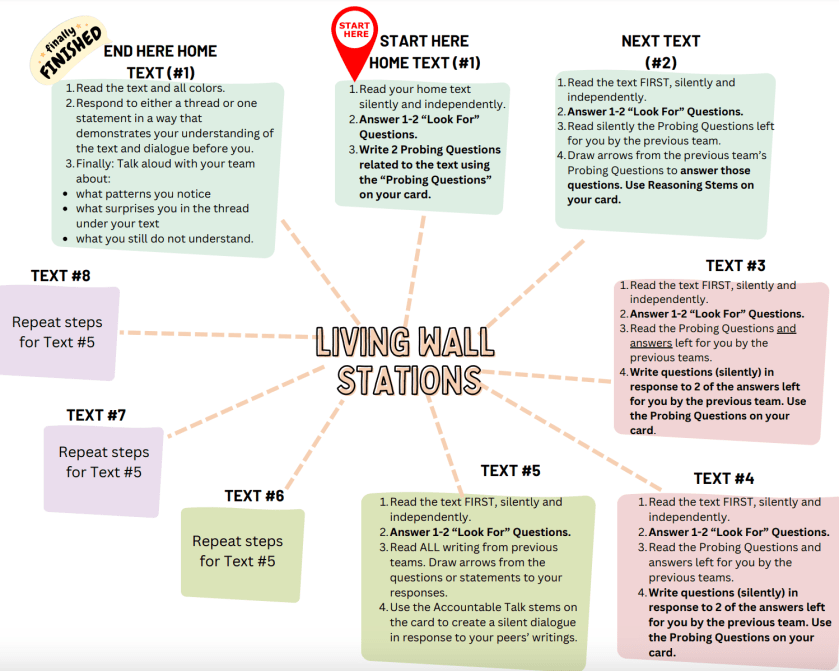

At the top of the paper, space out the 10 or so text pages (see images below). I also number each text page for reference

Add to clipboards the Living Wall directions page, Criteria for Success, probing question stems, and a questioning matrix (pictured below).

Display vocabulary posters from the previous lesson.

- Learn more about all Living Wall resources and grab a copy of the file for your classroom.

“Living Wall” Step 3: Launch!

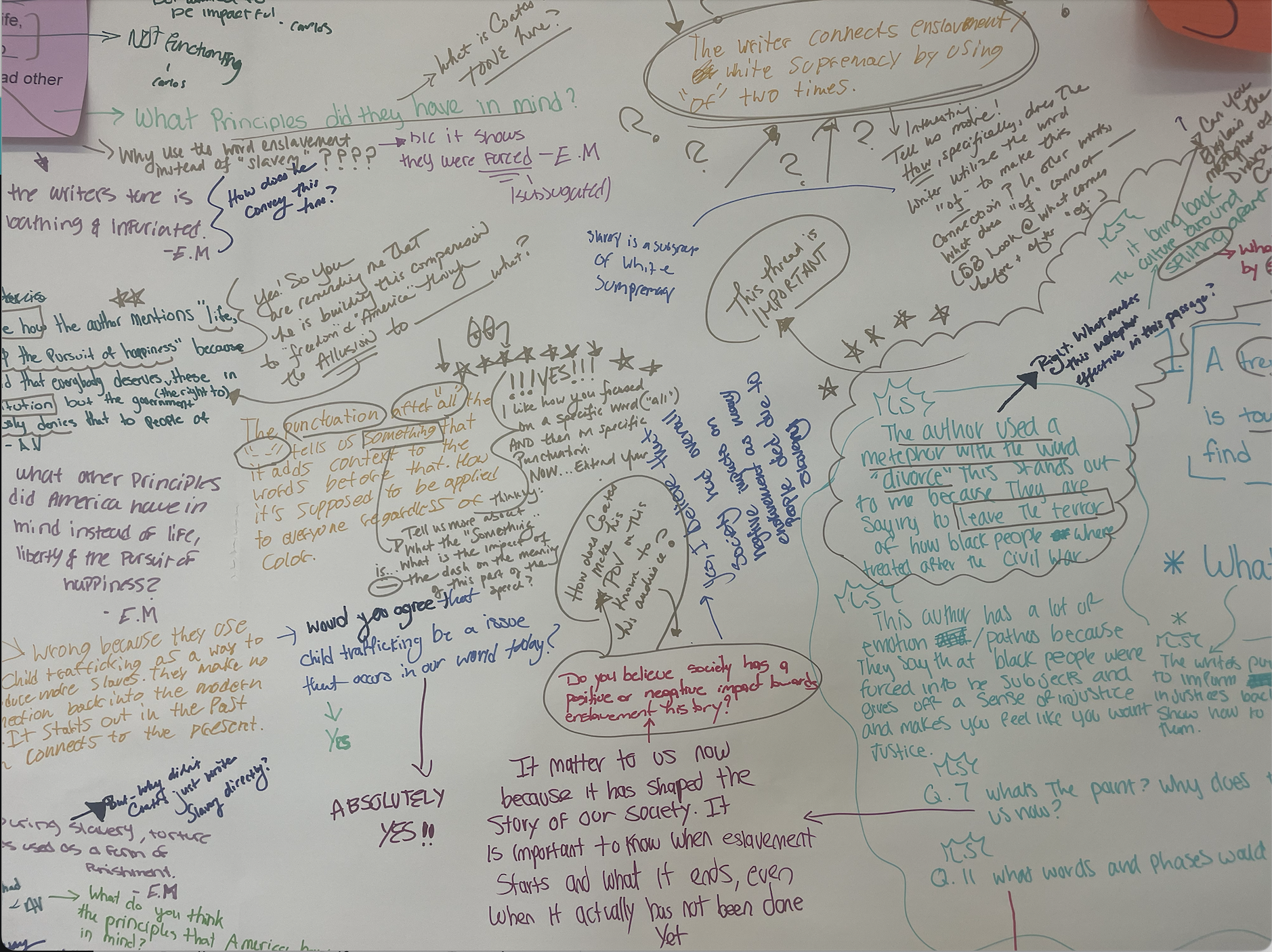

The Living Wall serves the primary purpose of critical and close reading (students read the same text multiple times through different lenses) and works great for complex text as a first touch-point to the text. The questions and stems on the cards pictured at right offer a great tool for close reading look for’s in any discussion (silent or not) as well as in writing. The Living Wall requires discourse moves but in a silent dialogue, so students get ample (and literal) space to practice “building” on each other’s ideas. Students are encouraged to question each other’s responses in writing, drawing lines, arrows, shapes, circles. It’s messy because it captures the organic nature of the thinking and meaning making process.

The Living Wall facilitates “Building” as a Discussion Skill

I spent two class periods on the silent dialogue part of the Living Wall activity. It seems excessive, but two days provided time for students to reflect and respond to questions I left for them as feedback (directly on the wall), while allowing for three reads as part of close reading. I often jump over opportunities to facilitate building as a discussion skill. However, in order to “build” on each other’s ideas, students need to practice listening and “sitting with” someone’s contribution to determine how to apply someone else’s idea to their own. This is high DoK (Depth of Knowledge) as it requires synthesis and application often with differing perspectives. It’s also life skill. The Living Wall is a tool to support the discussion skill of “building” on each other’s thinking. Students rotate through the stations (there is no end or beginning station — just where each student lands). They move at their own pace and circulate the wall multiple times. They may need to be reminded of the “silent” expectation but then fall into a rhythm of observation, questioning, reading, and sitting with text. The pictures below are from a Living Wall with Ta-Nehisi Coates’s speech to the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on slavery reparations.

Text Analysis Strategies After the Living Wall

Students return to the text with new insight, and annotating with purpose for a focused skill, framework, or text “look for.” A framework go-to is Kylene Beers and Robert E. Probst’s Signpost annotation strategy and their book Notice and Note: Strategies for Close Reading. Check out pre-made Signpost (Notice and Note) task cards that my students use in “Text Teams.” Each student is responsible for teaching their group the text analysis “look for” on their task card. This is a great way to implement intentional grouping, differentiation, and scaffolding to support close reading and comprehension with complex texts such as Caste.

Something like the “3 Levels of Text Inquiry,” small group discussion framework is another option that gets at close reading and analysis within a small discourse community. Moving from the Living Wall silent dialogue to 3 Levels of Text Inquiry discussion offers multiple access points to analysis across different learning styles. At this point, you might decide to go back to the text for more independent reading with the book as a whole or specific chapters if you want to “slice” to serve your reading purpose, using the Living Wall as a pre-reading text activator.

Step 4: Using Wilkerson’s Text to Build Argument Writing for the Synthesis Essay

Interrogating the Text: “What assumptions does the text hold?”

The 4A’s Text Interrogation Protocol (adapted from The School Reform Initiative) is a great way for students to record their agreements, disagreements, and to zone in on the assumptions they believe are made, or are evident, in the text. This is a rich place for follow-up discussion either in small group or whole class as a space to probe “assumptions.” Remind students that these are not assumptions they have about the text, but assumptions they observe within the text. In nonfiction, this often means the assumptions of the author (and everything around the rhetorical situation), the data or evidence, first-hand accounts, etc. Interrogating assumptions is so rich, and you can take this in a dozen directions. I use it as an opportunity to probe students’ inference making and to get them to view the text as an entity with the ability to “hold” assumptions. With Caste, you can choose questioning that includes “the text” and/or Wilkerson herself as the “holder/maker” of assumptions.

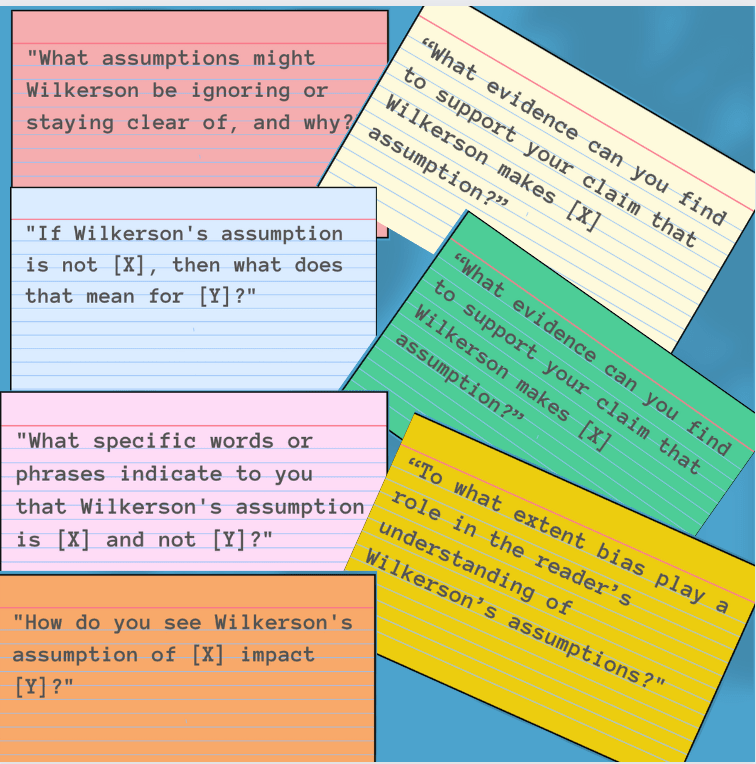

Questioning: the author and text as “holder” of assumptions

These probing questions work well on question cards for each team to discuss or for discussion in a Socratic Seminar. The point is to begin to weave the threads of Wilkerson’s arguments with students’ threads of meaning making and their own interrogation of Wilkerson’s text.

Try: Adapt these cards if you are working with fiction to “the character.”

Generative Thinking Rounds

In small groups, or independently, students identify what they define as the most provocative or resonating claim that Wilkerson makes in the part of the text they read. Students write that claim on chart paper, and all groups post their claims around the room in order to practice timed, generative thinking required of the AP Language Argument and Synthesis essays. If you don’t teach AP Language, this is still a fun way to gamify thinking.

Round 1: Set the timer for 6-8 minutes for each round (or less!). At claim/chart paper, students work collaboratively (or independently) to think of as many counter-arguments to this claim as possible, writing each counter-argument on a sticky note (if you can, color code sticky notes by team to keep track of each team’s work). Remind students, these are not necessarily their opinions; these counters are a brainstorming about what they imagine other people may say, think, or believe. If you want to give more of a challenge, ask students to post their sticky notes on the chart paper, leaving them visible for the next team. When the timer is up, students move to the next claim.

Round 2: At this second station, they read the claim, and then write all ALL of the reasons one may counter that claim left by the previous team. Challenge: no repeated reasons!

Round 3: Teams travel to the next poster, reading the claim and ALL the reasons/counters to that claim, and organizing the counters AND reasons from what they believe is MOST to LEAST important. Doing this timed is a fun way to up the ante.

Round 4: Travel to the next poster, read the claim, ALL the counters to that claim, and provide a rebuttal to each counter in support of the claim. (Ah-ha! What?) So, really, we are working backwards a bit. If students are confused, clarify that they are providing reasons to support the claim, but that each reason must “go against” or “talk back to” or “rebut/refute” the counter-arguments left by previous teams. That’s demanding! Alternatively, students can leave feedback for the previous teams in the form of probing questions until students reach their “home” poster. Grab a free questioning resource here.

Round 5: Students return to their “home” claim/poster to try to locate specific evidence for the argument created by the previous teams. This round is focused on the bits of source evidence they should take to either back up supporting points or refute counters to the claim. Students need to practice zooming in, isolating evidence (quickly, for the AP Lang exam), thinking about how the evidence serves their three points or counters to three points. You can do this timed or untimed. Sample slides to this activity are below.

Building an Argument Paragraph

Students can use argument stems to build a paragraph (I cut them up and laminate each stem on a strip, so that students can manipulate sentences). The writing purpose for this paragraph is for students to take a position either in agreement or disagreement to one of Wilkerson’s claims.

Caveat: I move students away from their own opinion about Wilkerson’s claims; this is important for the AP Language Synthesis essay (separating personal opinions from evidence-based arguments). When responding “on demand” to the AP Language Synthesis essay, students may or may not have an opinion on the prompt topic, but their job is to think of two different sides to the topic in the prompt and build three solid ideas to support one of those sides, while using the “other” side for counter-arguments in each paragraph. I always say, “If you are a lawyer, it’s often not your business what you feel about your client; you have to defend them.” In other words, argue positions, not opinions. I think this separation, or aiming for this separation, also raises the cognitive demand.

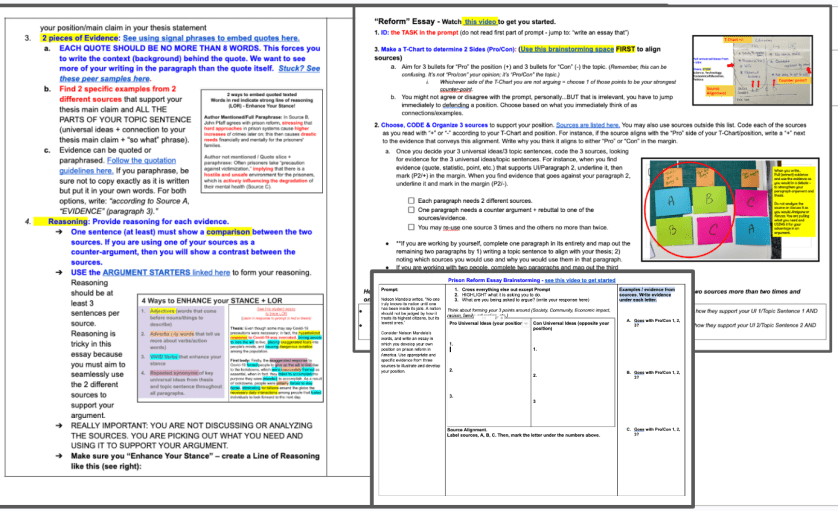

Utilizing Caste in Synthesis Essay Writing

Caste is the “launch” source for students as they figure out how to interrogate and evaluate evidence in their Prison Reform Synthesis Essay. Reading Caste to locate evidence for their essay provides a purpose and framework for navigating the text’s complexity. Grab all resources for the Prison Reform Essay here. I usually have students work in partners to draft the essay (the writing resource for this essay is pictured above). Students are provided with a list of sources and must follow the AP Language Synthesis essay guidelines (at least three sources; two different sources per paragraph; three body paragraphs). There’s a lot more on how to make that work in my Synthesis Essay materials, including the Synthesis Unit Bundle.

Caste to Teach Research Skills

Get students comfortable with searching for key ideas in the Index. When I taught the Prison Reform Essay using Caste, I suggested a student look through the index for “incarceration” or “prison reform,” and when those specific words weren’t listed, she immediately gave up. Caste as a research tool facilitates generative thinking: “Okay, if not incarceration, then…what is it when society incarcerates other members of society? What happens…” and start from there to pull out key words to search.

A mentor text for synthesis writing

- Locate passages with data to get students comfortable decoding data across many forms and evaluating HOW Wilkerson weaves data points to strengthen her thesis/argument/claims. Questions like, “What, about this data, specifically, tell you Wilkerson’s stance?” are great helping students spot the author’s position and how data downplay or elevate claims.

Students can isolate verbs and adverbs and question the connotation: “What does a negative connotation tell me about the stance in this text? Do I notice a connotative trend (mostly negative or mostly positive) associated with a particular claim? What might that indicate about that claim and the author’s stance towards that claim?” That is a lot of the decoding and evaluating required of students when reading across six sources on the AP Language exam and trying to pull evidence from a source to support or counter the position they are taking in response to the prompt.

- Locate passages where Wilkerson builds a strong Line of Reasoning. Students can locate different ways Wilkerson incorporates a word or concept with different phrasing, analogies, or synonyms. How do variations on a word or concept help to strengthen her argument / claim (or “enhance her stance”?) Students can trace evidence within a chapter to decide how the evidence supports the claim. Ask students WHY Wilkerson incorporated one type of evidence versus another and, “How would a different way of presenting this evidence change her claim or argument?”

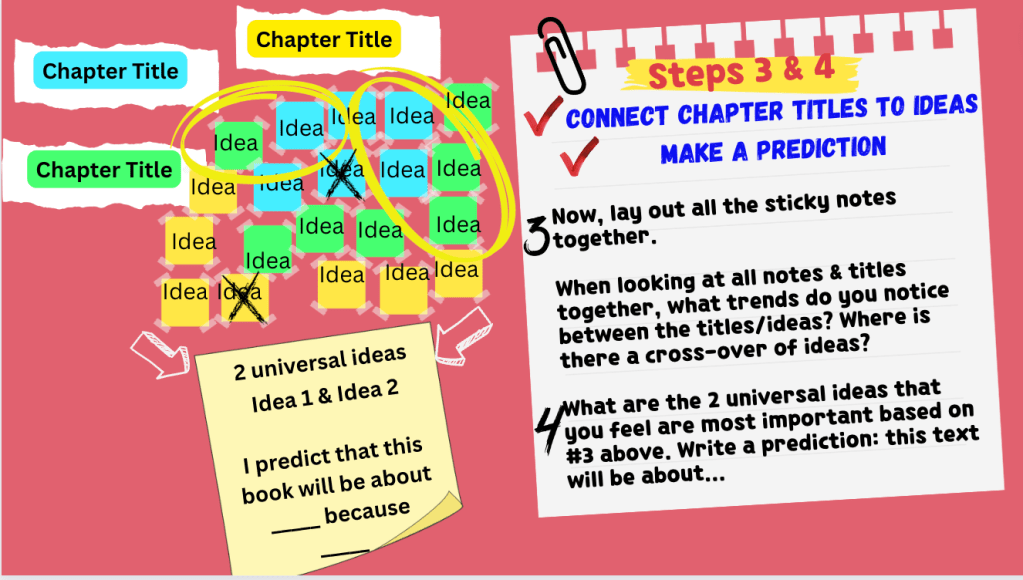

Text Structure

Analyze the way Wilkerson has designed the text structure and how the structure supports her arguments and claims. Caste offers the perfect canvas for text structure with seven parts, 31 chapters, and more than we might encounter in other books our students read. Ask: What’s going on with the italicized pages between chapters? Why would Wilkerson include those pages and in that order/location in the text? Students can do a lot with chapter sequence and titles–so much to probe! Check out the Text-to-Title work above that engages students by physically arranging, sorting, and tracing text, title, and ideas.

Always, the question is:

“How does [what we are examining] support Wilkerson’s thesis/claims/arguments and refute counter-arguments?”

Finally, how can we utilize Wilkerson’s writing–and writing in other complex texts–to teach students HOW to write? Check out The New York Times Sentences that Matter, Mentor, and Motivate for ideas on integrating mentor sentences. Wilkerson’s writing is rich with complexity and exciting ways to arrange words to build a line of reasoning and sustain her argument. I integrate sentences from Caste throughout the year in my AP Language class. Here are a few perfectly complex sentences from Caste that teach new ways to begin a sentence, build a sentence, integrate evidence, and arrange words to deliver strong imagery and effect–not to mention a strong message through analogy and juxtaposition:

“Just as pollutants don’t confine themselves to the air around a factory, this single caste inequity has spared no one.” (Caste, 188).

“WE owe our misperceptions about alpha behavior to studies of large groupings of wolves placed into captivity and forced to fight for dominance or to cower into submission.” (Caste, 205).

“Neuroscientists have found that harboring this kind of animus can raise a person’s blood pressure and cortisol levels, “even during benign social interactions with people of different races,” wrote the neuropsychologist Elizabeth Page-Gould.” (Caste, 304).

I’ll end with the arc of teaching complex text centered on building learning experiences around text with an eye always on equitable literacy.

More on enabling text to bridge the gap towards complex text soon.

I hope you and your students find these strategies helpful when working with Wilkerson’s Caste.