As a teacher of 10th grade ELA, I understand the urgency of six short months. The MCAS, feelings aside, is a reality for classrooms, schools, districts, and above all, students and families. In Boston, MCAS Bootcamps rallied students to attend full school days over February vacation and refocused students on a common goal. Whatever metaphor I use with my students (MCAS is a competition, a video game, a sport, etc.), the test is a literal marker of a student’s access to life beyond high school for college and career. So often, schools that explicitly teach test literacy are shamed (and by test literacy I mean: How a student reads and consumes and negotiates the test with agency and awareness). These are the same schools that are criticized for “teaching to the test.” My goal with this post is by no means to be political, but I do think it’s important in my practice to name opportunities for explicit instruction to empower students, and teaching the literacy of high stakes testing, I believe, not only empowers students as test takers, but as critical thinkers and consumers of information when accessing and achieving the very standards that the MCAS (and SAT, and AP) are assessing.

Big Picture: My job as a teacher is to facilitate student access and achievement, and I want that access and achievement to be standards-based. [But/and], the immediate window of opportunity as a tenth grade teacher is six months from where each student is at when we meet in September.

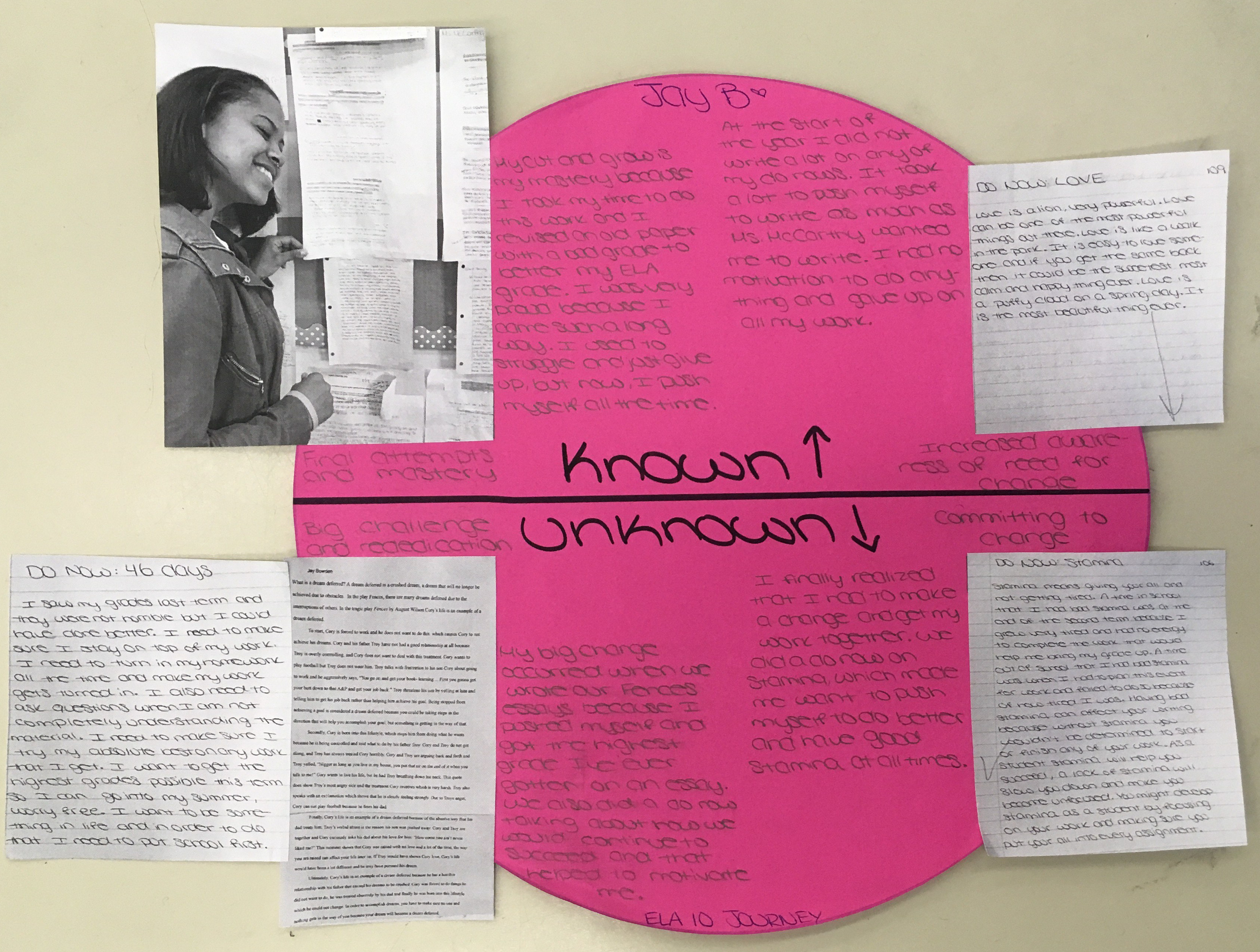

From where each student is at… So, what can I control? What and how I teach, and how I readjust my teaching with fidelity.

What if I flipped my thinking and didn’t see “teaching to the test” as a be all, end all deficit? Having taught in different types of secondary school settings as well as in higher education programs, I know that test literacy is a crucial skill extending well beyond MCAS. I believe it’s a life skill. It’s a skill in making explicit what is often implicit: cultivating and sustaining self-efficacy and agency in high-stakes situations. Since I began teaching, I’ve experimented with ways to making learning as explicit as possible–not because it makes the work of learning easy, but because it makes the work of learning a transferrable and lifelong skill.

This past fall, I adapted ELA MCAS “boot camp”-style curriculum for English Learners who were retaking the November ELA test. (Day 1 and Day 2 slides of the 5-day session are linked here). I used choice writing frames like this to help make writing tasks on the Legacy MCAS explicit. I realized that I needed to peel away the layers of text inherent in the MCAS to make meaningful words such as “elicit, demonstrate, decipher, explain, reasoning.” Students may understand fully the word “explain,” but what is the success criteria of the word “explain” in a written response versus a reading passage question on MCAS? And, what agency does a student feel when encountering the command “explain” when asked about character change from beginning to end of an excerpt (and what does the word “excerpt” mean to me on this test)?

I think consciously about student agency and implicit bias in many forms, and high-stakes testing in particular. As an ELA and ESL teacher, I try to find ways to teach the layers of text within a test like MCAS. What can I do to facilitate my students’ ability to navigate those many layers of text? That’s a question that pushes me when working with any text. So, I began to change they way I viewed MCAS by teaching the layers of literacy within the test. This year, due to timing, I experimented with virtual sessions on Google Classroom and YouTube. It’s far from a solution, but it is an interesting dilemma to consider, politics of standardized testing aside. As an ESL teacher this past year, I began to unpack the relevance and urgency of demystifying the complex layers of literacy a student needs in order to move between home, school, and work with friends, family members, teachers, lawyers, counselors, bosses, doctors, store clerks, pastors, bus drivers, etc…..the web of literacy we encounter when moving between different worlds defines our levels of interaction and our ability to function in each world. Because of this, I don’t see the explicit teaching of test literacy as “teaching to the test” so much as it is teaching literacy in its many forms, facilitating student agency to become critical consumers to uncover what needs to get done, where, how, and why.