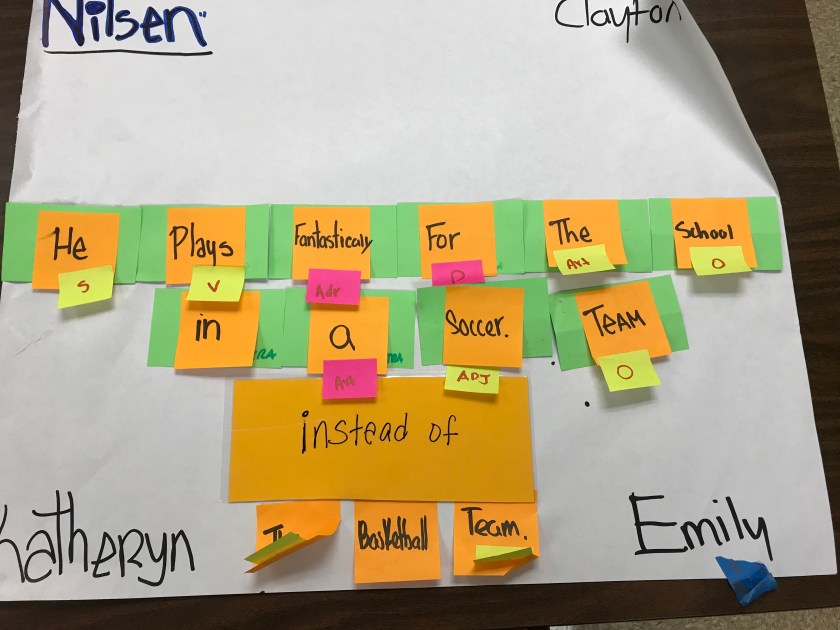

One of my favorite ways to look at the word, phrase, and sentence levels in writing is a Sentence Building or Organizing activity that relies on physical manipulation of language parts. A video of my ESL3 students working with this activity is linked here. These activities facilitate student-centered learning in teams as a way to help students not only dissect sentence parts, but use sentence parts in various ways when building a sentence. I developed this activity as a way to engage students beyond the Chromebook, in teams, and with their “hands.” I wanted students to feel not only like they were in control of language, but that they were empowered to make decisions to build complex sentences with prepositional phrases in different ways. This activity came out of a learning I had from previous lessons where students expressed hesitancy with “playing with language.” I wanted students to feel that they could be decision-makers when writing sentences and that sentence composing is similar to moving around pieces of a game or puzzle. This activity also focused on our unit’s social objective (listening to the speaker, eye contact, and speaking so others can hear you).

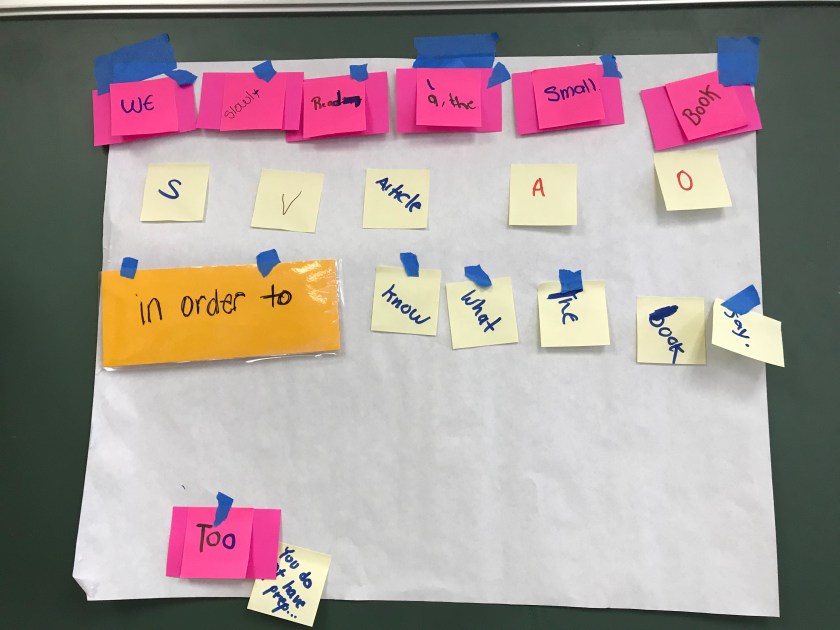

Organizing Sentences Activity- This activity was a formative assessment (I called it a group quiz) to our Sentence Building activity. Now that students practiced building sentences and demonstrating self-monitoring and decision-making when sentence composing, I wanted students to become comfortable with sentence complexity within the data unit content by using parts of a complex text (from a scientific article about climate change) to rebuild, or put those pieces together again into a sentence that makes sense coherently and logically. I wanted students to work together, show what they know in terms of sentence parts, sentence combining, and prepositional phrases to compose complex sentences, and also to push each others’ thinking with targeted questions. Each team received a large envelope with the full directions printed here. Each team received a set of cards (also printed here) to help facilitate academic discourse, which, in turn, helped to facilitate students’ language and content development. Each person on the team practiced accountability by taking on a role related specifically to the academic skill of group discussion. Before the activity, we practiced different questions that each role/student would ask in his/her team according to pre-printed discussion cards. The Organizing Sentences Activity directions are linked below. I have also included pictures below. This lesson pushed students to feel what it’s like to solve problems within a group when there is no “right answer” in front of them. As I walked around the room, I questioned students’ choices regarding phrase/word arrangement as they rebuilt their sentence from pieces. “Why did you decide to use that phrase after this word?” “What is your next step in this process?” “What’s another way to say/write this sentence?” “How can you backup your decision?”