As a member of the eight-person 2016-17 Calderwood Writing Fellowship cohort, I worked with teachers across the state for one year to develop my own writing-based inquiry. This experience provided the space for me to approach teaching as a researcher and writer; I incorporated research in the field into my lessons to test my inquiry question: How can I utilize a teacher’s sense of urgency to build students’ writing stamina and overall academic resilience? I worked with my students that year in a different way than I had any other year: I began to view my teaching as a collaborative and reciprocal process with my students. Through the teaching of writing, I began to unpack my students’ writing resistance and rebuild their relationship to writing from a strengths-based perspective.

By focusing on my students’ assets, I re-designed the way I taught writing to incorporate partner and group writing (I was excited to find research that pointed to the strong connection between orality and literacy and talk with writing development).

A group essay planning and strategy workshop to build skills in evidence-based reasoning.

I also focused on the impact of my role as a writing teacher, thinking very carefully about how to scaffold and differentiate writing for students of varying learning and language backgrounds. I utilized feedback loops, probing questions, and 1:1 conferences, practicing ways in which I provided descriptive feedback. I engaged in dialogue with my students about writing to encourage their identity as writers in 1:1 conferences, group writing workshops, and written feedback via Google Doc comments. I also utilized tried-and-true pen and paper comments as a tangible document of my feedback.

My inquiry with the Calderwood Fellowship not only changed the way I taught writing, but changed the way I taught…period. The research validated my natural instincts to approach teaching as a relational practice, and specifically, the teaching of writing as a facilitative, process-based approach. Yes, of course the writing product (the essay, speech, or opening statements in a debate) is a crucial component to assess a student’s writing, but the steps to get to that product (brainstorming, extending analysis, drafting a thesis, writing multiple drafts, revising, editing, sharing, publishing…) are what I look for to demonstrate a student’s writing growth. I also utilize the writing portfolio system, where students cultivate writing over the year to document and reflect on writing choices and writing progress.

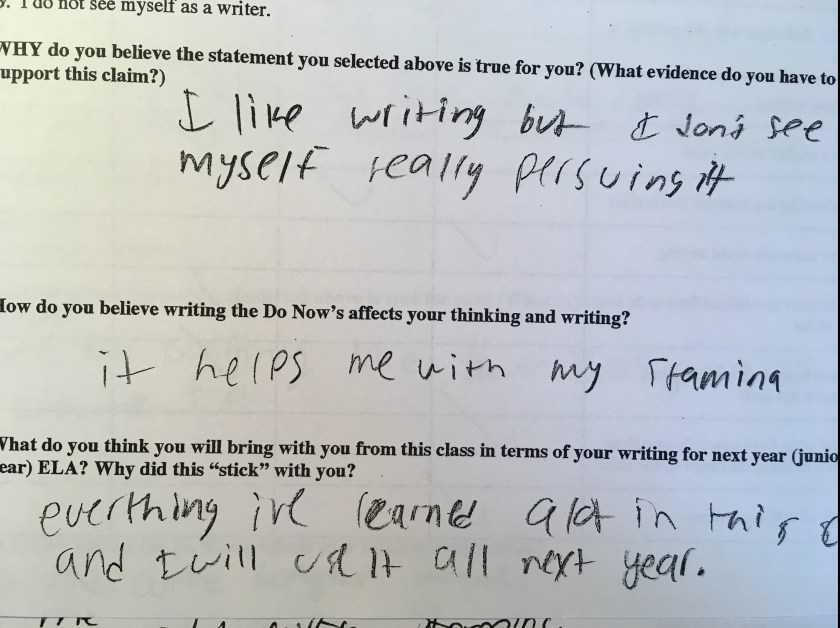

As a writing teacher, I wanted to find ways to break down barriers to writing by unpacking and demystifying the process of getting thought to paper. My students practice and demonstrate resilience as a life skill, and I wanted to see how I could bridge that life skill to an academic skill through writing. I started by transforming the Do Now activator into an activity to reframe the classroom as a space for reflection and inquiry. As a tenth-grade teacher preparing students for the ELA MCAS, I wanted to use the Do Now as a tool to build writing stamina in an on-demand writing environment. I relied heavily on expressive writing in the Do Now space and regularly utilized reflective writing in the Do Now as an activator to more analytical, text-based writing later in the lesson.

As part of my Calderwood inquiry, I stumbled upon the Cut-and-Grow writing revision strategy–a SIOP model strategy for English Learners. (See Cut and Grow Directions and Cut and Grow highlighting ingredient list.) As a teacher of many English Learners at various points of English Language Development, I jumped at the opportunity to engage my students with writing and revising in a way that incorporated the physical manipulation of language and parts of the essay. Many students remarked that the Cut-and-Grow activity was the pivotal activity that helped them extend analysis and understand how analysis is used to strengthen a thesis in a formal essay. Examples of the Cut-and-Grow process and product from my students are included below.